Collab:Taukan

This page is dedicated to the design of the Taukan article that focus on both the Taukan language family and the Taukan ethnic groups and culture.

Introduction

The Taukan Project is an attempt to create a cohesive story for Central Antarephia by establishing a set of agreed upon historical, linguistic, geographic, and cultural facts. This forms a framework which mappers can use to connect to a wider accepted history, while still allowing flexibility when describing and mapping their own territories. The main goal is to create a story that makes sense, as much as is possible.

The Taukan Project only applies to voluntary members and their territories, although the hope is that additional mappers will join in this shared history, and that it might expand to other parts of the OGF map.

Generalities

The Taukan Collaboration focuses primarly on Central Antarephia, on both sides of the continent. The Western Coast becoming dryier to the North, S35th/30th parallels would be a natural limit for the Taukans extension to the North. East of the main Antarephian mountain ranges, the Taukans come into contact with peoples speaking Antarephian languages. This does not preclude any form of mutual influence on cultural, historical or linguistic topics with the latter.

Countries

Below is the list of countries that are part of the Taukan Sphere, culturally and/or linguistically, and form part of the collaboration:

| Name | Status | Owner |

|---|---|---|

| Guai or Wiki article | owned territory | Aiki |

| Kōpers̨iā ā Alējȅverdi or Wiki article | owned territory | KameKaza |

| Osaseré | owned territory | ruadh |

| Ullanyé or Wiki article | owned territory | ruadh |

Naming

Taukan from the old Taukan root tauka implying an idea of bond or meaning those who are bound by an oath. This name may have been apply by the early Taukan tribes upon themselves as they constituted some kind of loose federations.

General History

Paxtar was a country and owned territory spanning roughly over AN139, AN136c, d and e. In the below sections, its mention would be adapted

Origin of the Taukans

The Taukan cradle is thought to be located in what is now northern Sabishii in Paxtar. Archaeological remains of a neolithic culture unearthed near the bank of the Şibār River are the oldest remains of human presence to be found in the region. This population expanded south towards the coast and left artefacts, mainly pottery and post-holes where settlements had been located. This area is considered to be the original homeland of the Taukan culture. In a series of migrations they spread west along the coast, reaching modern-day Guai during second millennium BCE. In a later migration a group moved east across the central Antarephian mountain range to the Asperic coast, reaching Ullanyé around 500 BCE. They spread throughout central Antarephia, merging with preexisting cultures they encountered.

Taukans migrations

Southern & Eastern migrations

Around 1500 BCE, Taukan tribes had colonised most of today's Paxtar. A first group migrated over the XXX Pass over to the Large Northern River Plain, passing through territories inhabited by Sabishian populations. Over the next 5 centuries, Taukan populations spread alon the rivers and the Asperic Coast of AN137f and AN144 Territories. Around 800-700 BCE, a second group of Taukans left Southern Paxtar and reached AN142i Coast and moved up the Large Yellow River Plain. They met the first in what is today's the AN148 Territories. Despite cultural and linguistic influences, the south-easternmost tribes of the second group were slightly less affected, giving to today's AN148, AN152b, Ullanyé and Osaseré, their distinctive Taukan flavour. By the 4th Century BCE, Taukans had crossed the Trinity Strait over to Ullanyé and by the end of the 1st Century, Dyákunda and Moda Benyé Civilisations had completely merged with the dominant Taukans.

Western migrations

Taukan tribes that have been established on Gonfragerran coast, started to move westward, reaching Guai between 2,000BC and 1,000BC. Some of these tribes' name are known as they kept written archives of some of their activities (namely, trades and political decisions). Their Abugida writing system has been in use until the late 17th when Romantian alphabet superseded it completely. By 500BC, the indigenous Kaitese people had completely fused with the Taukan tribes, leaving some oronyms and hydronyms still existent, and agricultural techniques previously unknown to the Taukans. Taukans organised themselves in a set of city-states usually ruled by a council of the elders. These city-states are usually divided into those based agriculture and/or mining, and those dedicated to trade by sea or land routes. This period, lasting from 500BC to 200 AD, is known as the Silver Age.

Early Modern and Modern History

Timeline

General Culture

Urbanism

In most countries, settlements tend to be rather European-looking. Historically speaking, a lots of Taukan cities and major towns were built around three plazas, sometimes called the 3 circles, the 3 fires or the 3 cores depending on the country and culture:

- A commercial plaza for a market that had traders, town houses for the rich, closest to the town port in case the town has one.

- A governmental plaza for official gatherings and announcements with law courts, town halls, central in the town.

- A plaza for the plebs with religious buildings, bathhouses, food, entertainments

In some countries or places, plazas 1 and 3 are merged.

Sport

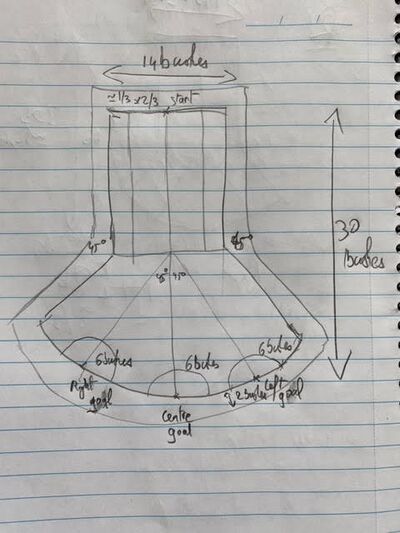

The following discipline was once extremely popular but is now a secondary discipline on most Taukan countries. The idea behind designing a new sport is to map something distinctive in our countries. We thought about something that could easily played, loosely inspired by Azteca and Basque pelotas. The sport is named Rapu in Guai and Rabú in Ullanyé. The pitch is strongly inspired by the "R" from Tenibri scripts and it size is loosely based on Box Lacross pitch: not too big, not too small. It is 30 bushes long and 14 bushes wide (56.1x26.18m). The corridor occupies half the length (15 bushes). On its bottom end is located the centre of the the bottom circle, cropped at 45° from the corridor's width. Side goals are placed at 45° from the centre line as well. Additional lines are present: 6 bushes around the goals (To be honest , just the rough distance between two points generated when creating the circle), and 2 vague 1/3 2/3 parallel lines in the corridor (same, picking closest distance between on the circle having the corridor's width as diameter). Supposedly one team starts at the top end and tries to mark by throwing a ball of some sort in/on one of the goal (is it a cage, a rod, a loop?), supposedly x on the centre one and y on both side ones, the other team trying to block them and throwing the ball back to the start point. "Official" measurements are given in the traditional Taukan system of measurements.

You may find examples of pitch or stadium below:

Beliefs and rituals

Traditional Taukan beliefs are often regarded as a nature religion or an amalgamation of religio-philosophical traditions, although in most cases, they do not consist in an organised religion. Varying from place to place, their practitioners tend to believe in spirits, souls or power of places and beings. In some version of these beliefs, the universe is alive, aware but indifferent. They believe that believe that the natural world, and all living things within it, should be respected, otherwise the universal balance would damaged.

Shrines or temples exist mostly near bodies of water or springs, deep woods, cave and remote hills and mountains were believers or not can spend a short contemplative moment or a longer retreat.The shrines are generally located in scenic spots of natural beauty or seclusion, with the larger and more accessible ones favoured for weddings and funerals. Some local version of those beliefs (e.g. Ohoism in Guai) think that it is some form of self-obligation to more or less regularly visit those scenic spots: seeing natural beauty, watching water running away are thought to appease the mind, clear problems away and to contribute to universal balance.

A lots of Taukan temples have a circular shape or include a circle somewhere in their architecture (e.g. round courtyard, garden). A 2000-year-old example can be found east of Cacamarr, Ulannyé. Kimí Tauka or Summit of the Biding is a stone circle with an associated spring estimated to have been erected around 500 CE. Kimí Tauka was classified as a Historic Site in 1897 and as a Cultural Monument in 1983.

Spirituality and traditions

Taukan spiritual concepts

- Eight Virtues

The Eight Virtues are traditionally listed as: Courage, Rectitude, Benevolence, Loyalty, Diligence, Humility, Temperance and Respect. Originally, they were expected from those who ran the city or state, but over the time, they have been taught as basic virtues of any person of integrity and honour.

- Circle

Circle or circles usually represent perfection and plenitudes but can also relate to the old idea of tauka that implies an idea of bond or meaning those who are bound by an oath. This name may have been apply by the Taukan Peoples upon themselves as they constituted some kind of loose federations.

- Taukan blue

Celebrations

- Remembrance of the dead

Remembrance of the dead is usually observed sometime after the autumnal equinox. In Guai this day falls on the first Thursday of April.

- First Rains

This celebration is particularly meaningful in Northeastern Taukan regions affected by dryer summers and sometimes droughts. It celebrates the first heavy rains after summer. In Guai, this day falls on the Friday following the Remembrance of the dead day (falls on the Thursday). Rain or water in general is though to purify the mind and to take the sorrow away.

- Winter Solstice

In Paxtar, this day is celebrated as New Year Day

- Winter blossom day

Wattle blossom day is an important Winter celebration in Northeastern Taukan regions. One species of Wattle has its flower as the national flower of Guai or hāni. This day is traditionally observed early or mid-August, depending on the region.

- Vernal equinox day

This day is celebrated in Guai and Paxtar.

- Children's Day

This day is observed in Guai on the first Monday of October.

- Summer Day

Summer Day is traditional observed in Guai on the first Monday of December.

Folklore

Below is listed a small sampling of types and examples of verbal lore:

- Aspra

Aspra mythological shield that threw projectiles back at the attacker. The story seems to originate from the Kaitese People Mythology as this concept is not found in contemporary Taukan culture. Long forgotten, its popularity rose at the time the Taukans came in contact with Ulethan colonists and its fame spread across the Taukan culture sphere. Aspra can be manned only by those demonstrating the Eight Virtues

- Kidjo & Cilia

Kidjo & Cilia (usually transcribed as Keejoe & Sheilia in Ingerish) are a pair of swans living on a pond, filled with water so pure it gives immortality to the purest souls who drink it, yet it induces envy and frustration to the others. The pair, of an undefined colour, can speak and is endowed with immortality, implying their souls are the purest.

The pair is approached by a human couple that lives nearby. Unaware that human souls can never be completely pure, Kidjo and Cilia offer them water and other gifts, and start teaching them how to speak. Days after days, the swans become more and more colourless (whiter and whiter in some versions) as the humans become more envious of the swans' gift (which is the ability to speak), and display eagerness to learn more and more.

Meanwhile Kidjo and Cilia lose their own ability to speak to the point that even their own names become those of the two humans, unnamed until then. Furious at mankind, the swans retreat and, from then on valiantly defend their cygnets against any human intruder as they do not trust them anymore.

By the end of the story, Humans know how to speak but are envious, easily frustrated and usually do not know what to do with this ability apart from being slanderous.

In Guaiian, moho kidjo or swan tear means to mourn for something dear one has lost without having fought for. Moho Kidjo is also a highly alcoholic spirit produced in the Táriao Upland (southern Guai). Moho Kidjo is transparent with a light blue hue, and its sale and consumption were severely restricted during most of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Kidjo (/'kidʒɔ/) is cognate with Guaiian kidj (/'kidʒ/ - seven) and Olonyé kidynó (/'kidʒo:/). The root /k/+/dʒ/ conveys some meaning of speaking or causing someone to speak. In old epic poems, phrases such as "open my lips" are frequently affixed to Kidjo or kidj (number seven).

The swan is the national bird of Guai where it is admired for its natural grace and its fierceness to defend its kind.

- Kirakó

A spirit whose name is roughly translated as "the one who does not look exactly similar" and features in several Taukan mythologies. Kirakó often acts as a guide, adviser or judge and many of the tales revolve around the spirits obscure oracular pronouncements. It is associated with nocturnal animals, especially owls, and often frequents pools, hillsides and high places. It has many physical forms and is rarely described in the same way twice. A central motif of the Kirakó stories is that human protagonists are unable to recount in any great detail what the spirit looked like.

In Guaiian versions of the lore, Kirakó (/kiɾa'kɔ/) is most exclusively associated with owls, especially the white-faced barn owl, living by a pool or the entrance to a subterranean spring, whom the hero or heroin is due to come visit at night or happens to encounter. In these encounters, Kirakó, sometimes acting as a guide, always tells the very truth. The rub lies in Kirakó's rather oracular parlance that is usually misguiding. The hero runs from mishaps to tragedies and sometimes dies by the end of the story. The moral of the story is usually understood as beware of well-intentioned beings or beware of the interpretation one gives to others' words.

The meaning of the -ko ending has been lost. On the other hand, ki stem usually conveys the idea of to see, to look or to resemble, and -ra is a negative suffix. Given its behaviour in the Guaiian versions and in addition to "the one who does not look exactly similar", Kirakó is also understood as "the one who does not see the same things/same way", implying the bird is blind, clairvoyant or see the same things but in a different way. The quirk of this story was extremely popular during the 19th century, at the height of the Romantic era, to the point that women started wearing jewellery pieces that depicted Kirakó, usually with gems such as moonstones set in silver.

- Mona

Mona is the story of a kind-hearted mother Raven. In Guaiian, the raven's name is spelt Mw̄na (/'mo:na/). Both Mw̄na and Erói(/e'ɾɔj/), Guaiian for raven, have remained popular female and male first names.

- Tasóndy

Literally, 'stars in his back' is a mythical being from early Ullanyé religious tradition understood to act as a mediator between the conscious and unconscious mind or dream-state. He is one of the Fading Band who are believed to influence the course of a person's life. Tasóndy usually appears as a marine mammal in the myths, occasionally as a dolphin but more often as a one of the larger whale species. He is strongly associated with the sea, sailing and fishermen. The Sindyé Tasóndy is named after him.

- Taukiri

Taukiri, also known as the Weeping or the Mourning Maiden, is popular tale originating on the coastal regions along The Koropiko bay. From place to place the plot varies but the popularity of the tale has inspired poets', novelists' and composers' works along the centuries.

Traditional system of measurement

The "need" arose when the traditional sport pitch was designed. Guai replaced this system sometime between the 1870s and the 1910s by the metric system.

| Name | Explanation | SI equivalent | Imperial equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 finger | finger width | 1.3cm | 0.51in |

| palm | 4 fingers | 5.2cm | 2.06in |

| head | 3 palms | 15.6cm | 6.14in |

| "specific type of bush" | 12 heads | 1.87m | 6.14ft |

| field | 60 "bushes" | 112.32m | 368.50ft |

| mile | 10 "fields" | 1,123.2m | 3,685.04ft |

| league | 4 miles (1h walking) | 4,492.8m | 14,740.16ft |

It is unclear, for the moment, which bush is considered. It could also be named rod or stick or anything 1.87m high or long for people living some 1,000, 2,000 or 3,000 years ago in Central Antarephia.

Languages

Classification

Basic features

Taukan languages have a number of shared features across all languages:

- Taukan languages are mostly analytic.

- Taukan languages have a fairly strict subject–verb–object word order.

- Verbal inflection is rather limited.

- Modality is expressed using modal verbs. Modal verbs are prefixed to the verb in some language subgroups.

- Taukan languages are genderless languages but use prefixes when gender indication is necessary.

Dyadyé languages

Dyadyé languages is a subgroup of the Taukan languages which includes Olonyé, spoken by around 6 million native speakers in Ullanne.

Gonfragerran languages

Gonfragerran languages take their name from the Paxtaren Province of Gonfragerra.

The definite article is not in use in the languages belonging to the Gonfragerran subgroup but suffixes are used to indicate plural notion. As in other Taukan subgroups, verbal inflection is limited. Tense is usually conveyed by a limited set of uninflectable suffixes, whereas mood is expressed by apocopated modal verbs prefixed to the verbal stem.

Kaitese languages

Kaitese languages take their name from River Kaita. Their main division are between Continental and Peninsular Kaitese languages.

All Kaitese languages make an extensive use of auxiliary verbs to convey both tenses and modality. The vocabulary contains a lots of pre-Taukan elements, mainly concerning agriculture and some natural features. The main differences between Continental and Peninsular Kaitese are:

- Peninsular Kaitese dialects: in the absence of nominal inflection, number and definiteness are convey by article, the use of inflected prepositions, the amount of pre-Taukan vocabulary compared to Continental dialects

- Continental Kaitese: extinct Old Iapan did not know definiteness article but used suffixes to convey number. Karnakian makes a limited use of articles for definiteness and keeps suffixes for number.

Peninsular Kaitese are furthermore divided between western and eastern dialects. Apart from minor vocabulary and grammatical differences, the grouping concerns phonology differences such as the lenition of western [ks] sound into eastern [s] or [z] sounds. For example, standard Guaiian eks (six) is esè in Taupan and Kinaran. Paxtar is Pasdār (/pas'dɑ:ɹ/) in Guaiian because the relation with this country was carried on by the eastern Guaiian Thalassocracies.

Cognates

| Cognate | Guaiian | Olonyé | Tenibri |

|---|---|---|---|

| /'kinib/ - KEE-nib - /wɔɾ/ - war area that freezes. From /'kinib/ area or scope, and /wɔɾ/ to freeze uor means frost in Guaiian |

kinvar /'kinvaɾ/ glacier |

kiníbar /ˈkɪni:'bar/ glacier |

|

| /a'wal/ - ah-WAL to move accross/through or to move forward From /'awa/ meaning "across, on the far side, beyond" |

avál /a'val/ ford |

abálú /abɔːɭu:/ fjord |

|

| /ɔ'lik/ - aw-LICK to gather/to assemble From /lik/ conveying the concept of "being together" |

àlik /ʌ'lik/ village |

ulik /ʌˈlɪk/ city |

ūlūç /uːluːç/ town |

| /im/ - im forehead or vertex Im still means forehead in Guaiian |

imaj /'imaʒ/ headland |

imás /ɪmɔːʂ/ mountain |

imot /ɪmot/ mound |

| /kaj/ - ki to flow |

oka /'ɔka/ stream |

okâ /ɔkɔː/ river |

oclát /okleːt/ stream |

| /'kɔdik/ - KAW-dik that which joins From /'ɔdik/, to join, and causative prefix k- |

kodi /'kɔdi/ lane |

kodik /ˈkɔdɪk/ lane |

pācod /pɔkod/ boulevard |

| /'pantjaran/- PAN-tya-ran to enclose/to pen/to limit Guaiian pantiar (prison) and bandiar (pen) derive from the same root |

banda /'banda/ border |

bandyá /ban'dʒɔː/ boundary |

pāŋje /pɔŋdʒɛ/ close |

| /pa'rajk/ - par-RIKE constricted |

barj /baɾʒ/ narrow |

beraig /bɛr'eɪg/ narrow |

|

| /sɔjd/ - soyd to flow/to run |

cuod /ʃwɔd/ canal |

chúhád /tʃuː'hɔːd/ stream |

|

| /'sufuθ/ - SOO-footh heat/flame Guaiian cif (fire) and sufuth (blaze) derive from the same root |

cufè /'ʃufə/ hearth |

sufú /ˈʂʌfuː/ house |

|

| /tɔb/ - tob high/to be high The root is also found in Ullanne District Caztobal |

dova /'dɔva/ hill |

dobâs /dɔbɔːʂ/ hill |

cobā /kobɔ/ hill |

| 1 | aiem /'ajem/ service |

ayemah /ajemah/ serve |

|

| 2 | alka /'aɫka/ tower |

aluchí /aɭutʃi:/ tower |

|

| 3 | atūl /a'tu:l/ vegetable |

atúl /aʈu:l/ green |

|

| 4 | avauc /'avawʃ/ wealth |

abos /aboʂ/ wealth |

|

| 5 | bahīr /ba'hi:ɹ/ cove |

ebahirí bay/cove |

|

| 6 | balw̄ /ba'lo:/ silver |

rabalól /ɽabalo:ɭ/ silver |

|

| 7 | bidji /'bidʒi/ factory |

bídyín factory |

|

| 8 Guaiian duyj (gold) derives from the same root |

cèdūk /ʃə'du:k/ treasure |

sadúek /ʂadu:ˈɛk/ gold |

|

| 9 | cireij /'ʃiɾejʒ/ general |

chiraig /ˈtʃɪr'eɪg/ wide |

|

| 10 | cyb /ʃɛb/ dirt |

seb /ʂeb/ grey |

|

| 11 | dasój /da'sɔʒ/ whale |

tasóndy /ʈaʂo:ɲdʒ whale |

|

| 12 | dekama /de'kama/ promontary |

dekama promontory/ridge |

|

| 13 | djom /dʒɔm/ health |

dyáhom /dʒɔː'hom/ well |

|

| 14 | djyr /dʒɛɾ/ pale |

dyer /dʒer/ white |

|

| 15 | edrala /ed'rala/ aquamarine |

edrala /ed'rala/ cyan |

|

| 16 | eigyb /'ejgɛb/ quay |

meraigebí /mɛr'eɪgɛbi:/ quay |

|

| 17 | eináv /ej'nav/ leisure |

enyabó /ɛɲa'boː/ leisure |

|

| 18 | emē /e'me:/ sky |

mek /mɛk/ blue |

|

| 19 | ēnia /'e:nja/ hut |

eiane /ˈeiɳe/ shelter/hut/tent |

|

| 20 | famí /fami/ turquoise |

fomí /ˈfɒmiː/ turquoise |

|

| 21 | fid /fid/ way |

fídyó /ˈfiːdʒoː/ way/pass |

|

| 22 | fobin /'fɔbin/ shop |

fábinú /fɔːbɪnu:/ commercial area |

|

| 23 | four four base/camp |

fór /ˈfoːɽ/ base/camp |

|

| 24 | fugū /fu'gu:/ mouse |

fugú /ˈfʌgu:/ mouse |

|

| 25 | gie /gje/ police |

gí /gi:/ police |

|

| 26 | isō /i'sɔ:/ archipelago |

isá /ɪˈʂɔː/ island |

|

| 27 | iwnerw /jo'neɾo/ plain |

yoneró |

|

| 28 | kadia /'kadja/ institute/agency |

kadyas agency |

|

| 29 | kadẃ /ka'do/ lagoon |

kadú /kadu:/ lagoon |

|

| 30 | kàe /kʌ'e/ data |

kue /ˈkʌe/ data |

|

| 31 | kas /kas/ shield |

gasa /gaʂa/ shield |

|

| 32 | kēbem /'ke:bem/ harmony |

tukebem /ʈuˈkebem/ harmony |

|

| 33 | kidjo /'kidʒɔ/ male swan |

kidynó /ˈkɪdʒo:/ swan |

|

| 34 | kukw /'kuko/ market |

akukos /ˈkukoʂ/ market |

|

| 35 | kūr /ku:ɾ/ pond |

kuré /ˈkʌɽeː/ pool |

|

| 36 | makle /'makle/ kernel/nuclear |

mekalén centre |

|

| 37 | noo /'nɔ.ɔ/ settlement |

ná /ɳɔː/ settlement/homestead |

|

| 38 | ono /'ɔnɔ/ plaza |

anyó /aɲo:/ place |

oco /oko/ place |

| 39 Orid means blood in Guaiian |

ōr /ɔ:ɹ/ red |

orid /ˈɔɽɪd/ red |

ordiç /oɹdɪç/ red |

| 40 | oros /'ɔɾɔs/ memorial |

oros /ˈoɽoʂ/ marker/memorial |

|

| 41 | pūskel /'pu:skel/ volcano |

' |

pūscel /'puskel/ volcano |

| 42 | rada /'ɾada/ brown |

rada /rada/ brown |

|

| 43 | ramú /ɾa'mu/ education |

ramú /ra'mu:/ school |

|

| 44 | recēgon /ɾe'ʃe:gɔn/ hospital |

reséregunyé /rɛʂeːˈrɛgʌɲeː/ hospital |

|

| 45 | rekigí /ɾeki'gi/ production |

rekigi /rɛkiˈgi/ industry |

|

| 46 | rimā /ɾi'mɑ:/ beach |

orimá beach |

|

| 47 | rod /ɾɔd/ lake |

irody /ˈɪɽɔdʒ/ water |

rod /ɾod/ water |

| 48 | ronós /ɾɔ'nɔs/ ridge/spine |

ronás ridge/shin |

|

| 49 | rwu /ɾow/ childhood |

ró /ro:/ children/descendants |

|

| 50 | saca /'saʃa/ sister |

echasa /etʃaʂa/ sister |

|

| 51 | sīj /si:ʒ/ forest |

isig /ɪˈʂɪg/ wood |

siç /sɪç/ tree |

| 52 | sonie /'sɔnje/ lamb |

sunyed /ˈʂʌɲɛd/ lamb |

|

| 53 | tce /tʃe/ hole |

deché /deˈtʃe:/ hole |

|

| 54 | tcydj tʃɛdʒ horse |

chedyedy /ˈtʃɛdʒɛdʒ horse |

|

| 55 | thos /θɔs/ opening |

tos /tɔʂ/ gate |

tosrine /tosɹɪnɛ/ cave |

| 56 | tis /tis/ sub- |

etis- /ɛtiʂ/ under/below/sub- |

|

| 57 | tondia /'tɔndja/ nature |

tondya wild |

|

| 58 | tūf /tu:f/ fox |

túfar /tu:far/ fox/dog |

|

| 59 | wabe /'wabe/ tern |

urabé tern, a species of |

|

| 60 | ugero /u'geɾɔ/ plant |

ukeró tree |

|

| 61 | wból /o'bɔl/ daughter |

ubál daughter |

|

| 62 | ycok /'ɛʃɔk/ farm |

esuk /ˈɛʂʌk/ farm |

resdūç /ɹɛsduːç/ land |

| 63 | yl /ɛl/ dock |

el /ɛl/ lake |

elc /ɛlk/ lake |

Sound changes

As an attempt to systematise the forming of words when borrowed from one language to another, I have listed the following "rules". As I did not pay too much attention when borrowing from Olonyé to Guaiian, these rules are not always respected but listing them may prove to be useful for future creations:

| Rule | Sound | Proto-Taukan | Guaiian | Olonyé | Tenibri | Guaiian example | Olonyé example | Tenibri example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | syllable | stressed /w/ | stressed /ur/ | uabe | urabé | |||

| 2 | vowel | /ɔ'lik/ | unstressed /ʌ/ | unstressed /ʌ/ | unstressed /u/ | àlik | ulik | ūlūç |

| 3 | syllable | stressed /ge/ | stressed /ke/ | ugero | ukeró | |||

| 4 | consonant | initial /θ/ in monosyllables | initial /t/ in monosyllables | initial /t/ | thos | tos | tosrine | |

| 5 | consonant | unstressed /dj/ | unstressed /dʒ/ | tondia | tondya | |||

| 6 | consonant | mostly stressed /ʒ/, sometimes stressed /dʒ/ | stressed /dʒ/ | dasój | tasóndy | |||

| 7 | consonant | /'sufuθ/ | mostly /ʃ/ in monosyllables or unstressed syllables. Sometimes /ʒ/ | /ʂ/ | /t/ | cif, imaj | sufú, imás | imot |

| 8 | vowel | syncope | unstressed /a/ in penultimate syllables | dje, makle | hadye, mekalén | |||

| 9 | consonant | /gj/ in monosyllables | /g/ in monosyllables | gie | gí | |||

| 10 | consonant | /pa'rajk/ | /ʒ/ | /g/ | /ç/ | barj, sīj | beraig, isig | ciç |

| 11 | consonant | many /g/ | many /k/ | ugero | ukeró | |||

| 12 | consonant | many /k/ | many /g/ | kas | gasa | |||

| 13 | consonant | metathesis /l/ for /ɾ/ or reversed | metathesis /l/ for /ɾ/ or reversed | metathesis /l/ for /ɾ/ or reversed | lyg, Karmelóm | reku | Cälmelom | |

| 14 | syllable | diphthong /ɔw/ | long /o:/ | four | fór | |||

| 15 | syllable | syncope of some unstressed initial syllables (prefixes that do not exist in Guai?) | saca | echasa | ||||

| 16 | vowel | stressed long /e:/ | stressed diphthong /ei/ | ēnia | eiane | |||

| 17 | consonant | /ʃ/ | /tʃ/ | cireij | chiraig | |||

| 18 | consonant | /a'wal/ | /v/ | /b/ | avál, dova | abálú, dobâs |