Pyingshum

| Pyingshum-sur | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| city | |||

| |||

| Demonym | Pyingshumian | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Riko Lazákom-Gomez | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 1312.6 km2 | ||

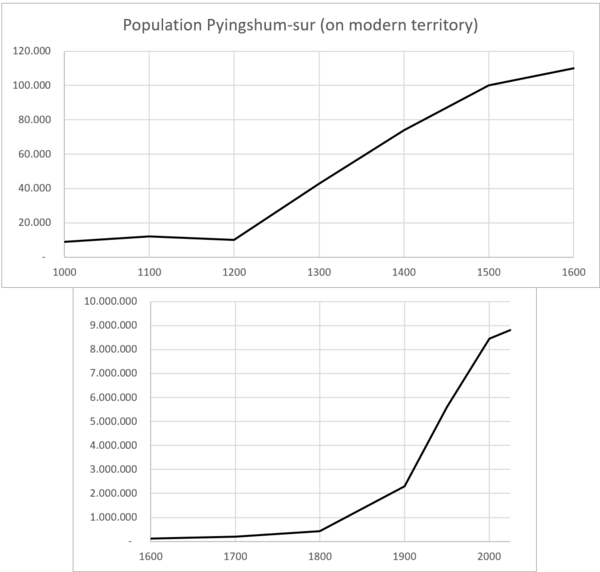

| Population | |||

| • Census (2020) | 8,000,000 | ||

| • Density | 6,100/km2 | ||

| Postal Code | 1000-1999 | ||

Pyingshum (pjiŋɕɯm) is the capital and largest city of Kojo. It is the country's centre of politics, culture and commerce as well as its main transportation hub.

Geography and Climate

| Pyingshum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The city lies on the bank of the river Kime. The terrain is relatively flat with only some smooth hills. The most notable peak is the castle hill on the old town, which provided an easily defensible shelter in ancient times. The terrain turns slightly more hilly away from the river bed to the north-west and south-east of the city. To the west of the city, the Zāle river ends in a protected wetland area. Pyingshum experiences humid subtropical climate (Cfa).

History

Prehistory

The area around today's Pyingshum was inhabited by various tribes without apparent cultural connections or language since the stone age. There have been findings of ancient tools and cave drawings as well as primitive clothing. Earliest housing and farming facilities found date back to around 6,000 b.c.

200 until 950: Tyússen

During this time the first small cities along the northern Kime were forming, amongst them the ancestor of today's Pyingshum, Tyússen. This settlement was developing on a major hill carved by the river Kime, which is today known as the Castle Hill in Kūtokkyaen-Pang. There are no physical remains of this city.

950 until 1249: PH

The region entered a temporary dark age due to intense wars. Several small potentates in the region tried to seize power from each other. Eventually, in the 1240s after a large battle, Abdi-Likk and his troops captured the city of Tyússen on today's Castle Hill. Damaged by the intense fighting, they started rebuilding much of the town in the following years. Meanwhile the Krun'a merchant family, who had more or less ruled over the city previously, managed to secretly gain support amongst opponents of Abdi-Likk, and prepared for a surprising re-capturing of the city. In 1249 they stormed the still unfortified city with the unified troops of many formerly hostile fighters, and killed all members of Abdi-Likk's clan. They built a new city, "Pyilsshum'yu", whose fortifications are still in place today as the inner city wall, enclosing an area of around 0.7 km².

1249 until 1620: Early Pyilser-krun'a Dynasty

The Krun'a clan founded the new Pyilser-krun'a Dynasty lineage, in which many of the collaborates who enabled the recapturing of the city were included via marriages and other arrangements. The city and castle on the hill continued to grow and generate revenue for the Pyilser-krun'a clan.

While at this time, the Pyilser-krun'a lineage controlled only an area of about 10,000 km² immediately around the city, it is this formational perdiod in which their administrative and military institutions developed that would allow them to go on and unify the modern Kojolese nation state in the 17th century.

1620 until 1668: The Thousand Kingdoms' War and Kojolese Unification

Main article: The Thousand Kingdoms' War and Kojolese Unification

The escalating war between the Kojolese kingdoms and a great famine in 1620 was also felt in Pyingshum. Due to a good balance of handling the mass influx of foreigners to the city and surroundings while at the same time upholding military strength against concurring kingdoms, Pyingshum was not as heavily damaged as many other major cities and emerged from the struggles in good conditions. Because the kingdom happened to do quite well economically and gained influence, Surb Rēkku from the Pyilser-krun'a dynasty intensified his aspiration to gain more control over the other kingdoms from the early 1630's on, and his kingdom expanded.

1668 until 1828: High Pyilser-krun'a Dynasty

After Kojolese unification under Surb Rēkku, Pyingshum became the capital of the new Kingdom of Kojo. The country entered a phase called "High Pyilser-krun'a Dynasty", which was marked by a large draw of administration, science and trade to the new nation's capital, where it flourished. The large influx of new inhabitants from all over the country into the already crammed city made Surb Rēkku commission an extension of the old city wall from the 13th century. He also initiated the construction of the "Beautiful Princess Nobun'ga Bridge" ("Mēonra Nabun'ga Kamul") in the new western part of the city, which posed the first permanent construction crossing the river in the area.

Around the beginning of the 19th century, advances in manufacturing and transportation accelerated the draw of people towards the cities and the capital in particular. For the most part however, the rulers were not concerned with mindfully facilitating this population growth, leading to a sprawl of slum-like conditions both within the city wall and around its edges.

1828 until 1939: Revolution and First Constitution

Despite the revolution and downfall of the monarchy being fuelled by rising dissatisfaction among the working class throughout all of Kojo, the decisive events took place in the capital. While it lead to the demolition of the royal palace ontop of Castle Hill, most parts of the old town remained intact.

After the democratic constitution was passed by the new parliament in 1834, it was decided not to construct the new government buildings in the old town, but to build a new planned city quarter to the north-east of the city, leaving behind the crammed medieval past. This was also done to leave room for future growth. The road layout as well as the architecture was supervised by lead city planner and architect Tunmaldu-Oejaén Ozuman. This area still attracts visitors today who marvel at the distinct Ozuman Style. While the new city would not be enclosed in another city wall, a ring of fortifications around 5 km from the city center - back then in the open countryside - was built to protect the city from potential artillery attacks. Although the city planners knew that over time the two city centres would grow together, the unexpected quick rise of industrialisation and the beginnings of the railway drew so many people into the city that it doubled in population in only a few years. Many railway termini sprang up all over the city. The first section of metro line 1 began operation in 1898.

20th Century

The first half of the 20th century is marked by constant growth, with new dense city quarters being either planned or growing organically at - what was at the respective times - the edges of the city. Beginning in the 1950s, suburbanisation begins to take place, with more and more new developments consisting of row or detached houses or some tower-style public housing projects. At the same time, mass motorization begins to take place, albeit at a slower pace than in other urban regions. During the 1960s, a motorway ring (G 100) around the inner city was built to decrease travel times and reduce congestion inside the city center. It was mostly constructed on open land from the fortification ring from just a little over a century ago.

In the 1970s, a shortage of large-scale office spaces in Pyingshum catering to global corporations was becoming apparent. Building modern skyscrapers across the city was perceived as undesirable, since this would have severely disrupted the city's skyline and architectural merit. Following the modern principles of functional structuring, a masterplan for the redevelopment of the southern part of the inner city was enacted. It included moving Aku-Dyanchezi from Doíku-Pang further south to allow for expansion and further consolidation of railway services, investing heavily into new automobile and public transit infrastructure, and to give modern architects a playground to build glass high rises in front of the relocated railway station on the area formerly used by railways and industry. Basic developments were finished alongside with the first office towers in the 1980s, and the last empty blocks were filled in the late 1990s. Due to ever growing land value and office space demand, old mid-rise buildings from the early stage of development are now increasingly being taken down and replaced with new towers, leading to a mixture of architectural styles from the 80s to contemporary ones.

City Scape

Architecture, layout and spatial planning, monuments

Demographics

Governance

Mayor and City Government

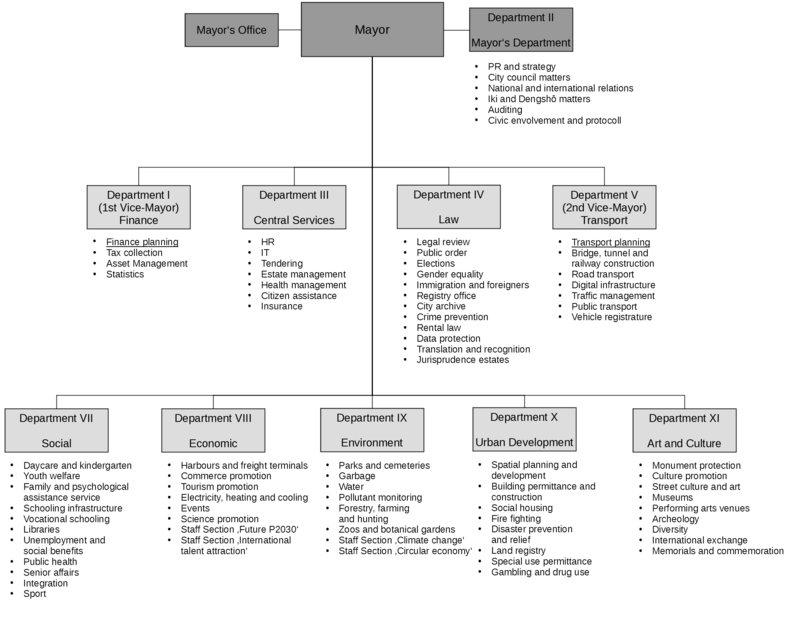

The mayor is elected by a city-wide popular vote with a run-off between the two strongest candidates in case no candidate reaches half of the vote in the first round. The current mayor, 54 year-old Riko Lazákom-Gomez, is not party-affiliated but attested to ideologically align with BF and AFK. He was elected in 2017. The term length is six years with no fixed term limit other than the mandatory retirement age of 70. The mayor presides over the city council meetings. The mayor's vote is tie-breaking. The mayor appoints the sub-mayors and decides on their fields of responsibility, however the city council has to approve them. As a result, the mayor usually tries to build a sort of government coalition with fractions in the city council and appoints candidates associated with them, similar to ministers in the national government. Unlike on the national level however, the mayor can formally give instructions to the sub-mayors. Also unlike on the national level, the sub-mayors usually (with the exception of I and V, who directly head an agency in their department which also aids in coordinating the other agencies in the department) do not command a dedicated agency akin to a ministry, instead directly managing their subordinate agencies. The organisation chart to the right displays the structure of Pyingshum's administration to the buéro-level. For detailed information about the role of municipal, regional and national governance, refer to the respective article.

After the 2022 council election, Mayor Lazákom-Gomez negotiated a coalition of MDK, BF and AFK. As aresult, the 1st Vice-Major is a MDK member and the 2nd Vice-Mayor from BF. The other departments were also handed over to different sub-mayors.

The Mayor of Pyingshum enjoys a high profile not only among the city's populace but on the national stage as well. With no autonomous territorial authority between the nation state and the municipalities, mayors and hibu-chiefs are the only major political voice underneath the national government - and, as opposed to the Chancellor, often elected directly by the electorate, such as the case in Pyingshum. Directly representing about a fifth of Kojo's population and leading the economic and cultural heart of the nation, the Mayor of Pyingshum is recognised in public discourse as about as relevant as important ministers. Historically, this is reflected in a strong rivalry between the Mayor of Pyingshum and the Chancellor of the Kojolese Republic, even when both offices were occupied by politicians from the same party.

City Council

The city council consists of 97 councilmen and -women. They are elected every four years by proportional representation in 10 multi-member constituencies. Those are congruent to one Dengshō each, with the exception of the inner city, which consists of one constituency north and one south of the river Kime. The number of seats for a constituency is proportional to the number of valid votes from that area and in the last election ranges from 5 (Zaelkom-Dengshō) to 23 (Dosyaeng-Dengshō North). In every constituency, every party or voters' association can put up a list of candidates for election, indicating the party's preference regarding their order. Independent candidates can also run in a single constituency and are, for the sake of casting and counting votes, treated like a list with only one candidate. Every voter can either cast three votes for any individual candidate(s) they like, even if they run on different lists, or cast all three votes for a single list with no regards to the candidates. The number of seats a list wins in its constituency is proportional to the share of votes for that list and it's individual candidates compared to all valid votes in the constituency. Every candidate that attracts more than 10% of their list votes as individual votes moves to the top of the list in order of the number of individual votes. List seats are then allocated to candidates in that order. If councillors leave the council more than 3 months before an election, the seat is filled by the candidate with the next most votes on the list. If a list is exhausted, the remaining seat stay empty, unless for independent candidates, where the voting power above the threshold needed to win a seat is reallocated to all lists in that constituency proportional to their votes.

The 2022 municipal election resulted in the following seat distribution:

| Party | Share of votes | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| RK (centre-conservative) | 23 % | 22 |

| MDK (social-democratic) | 20 % | 19 |

| BF (green) | 19 % | 19 |

| AFK (liberal) | 14 % | 14 |

| GD (socialist) | 11 % | 11 |

| GAN (authoritarian-right) | 5 % | 5 |

| MKL (nationalistic-ecologists) | 4 % | 4 |

| Independent candidates | 4 % | 3 |

Dengshōs and Pangs

Pyingshum is made up of nine boroughs (Dengshō), which in turn are divided into a total of xx Pangs. Unlike most other cities in Kojo, not all power is vested in the central city government. Pyingshum is one of only two Kojolese cities that have a second local layer of government on the borough-level. They have competences in the area of roads, amenities, ordinances, building permits etc. While elections of the local borough-councils are analogous and simultaneous to the city-council, the borough mayors are not elected by the people directly but instead elected by the respective borough-council. They are also not head of the local administration but instead perform mostly representative functions. Unlike the city council and mayor, sitting on a borough-council or being borough-mayor are honorary offices with expense allowances instead of fixed remunerations. The borough-councils further appoint members of neighbourhood-boards. They are made up of five to 30 adept residents of the Pang who advise the borough- and sometimes city-council on local matters.

For a list of and information about all Dengshōs and Pangs in the city, refer to the main article: Administrative divisions of Kojo#Pyingshum-sur.

Transportation

Key Data

The most common mode of transportation in Pyingshum is public transit, at 34 % of all trips. Private motor vehicles, walking and cycling follow at 28 %, 25 % and 13 % respectively. At 3.7, the average number of trips per day and person is slightly higher than the national average of 3.5. There are 320 cars per 1,000 inhabitants. 45 % of households, accounting for 62 % of the population, have access to at least one privately owned car.

Road

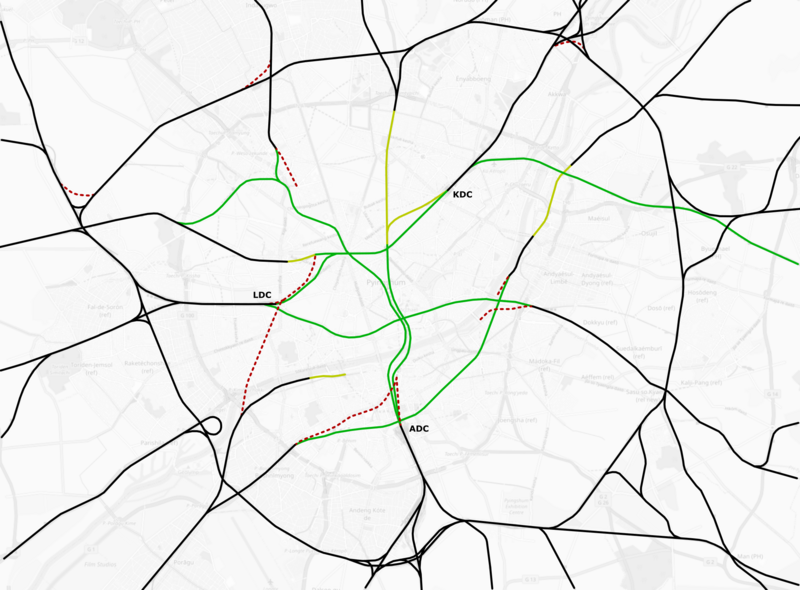

Many national motorways radiate out from the city. They end at the ca. 40 km long, central ring motorway G100 that encompasses the inner city. Several tangential motorways form a less circular, second ring of motorways through the suburbs.

Since the rise of motorisation, rising motor traffic has been dealt with in two complementary ways: on one hand the city tried to meet the demand by building high-capacity car infrastructure, mostly from the 1940s till 70s, often at the costs of local neighbourhoods. On the other hand, car usage in the inner city has always been discouraged in a number of ways. Since the 1960s, many narrow streets in central neighbourhoods have been turned into pedestrian and bike priority or only streets. The vast public transportation network has constantly been upgraded to provide attractive alternatives to the private car. There is virtually no free public parking, and high fees are imposed on car ownership in the inner city in general. Like on most national highways, users have to pay tolls to use them. In Pyingshum during rush hour, additional congestion charges apply which can up to double the toll or even quadruple the toll on the G 100 compared to the national standard. Most of the city is also designated as low-emission vehicle zone. It is possible to buy-out one's vehicle from this ban by paying, depending on the vehicle's emissions, a fee from 3,500 Zubi up to 15,000 Zubi (~600 int$) per month. The car sticker given out to these exempt vehicles is also known as "Daiamondoshi-medal", because most of them belong to a super rich elite who resides in Daiamondoshi-Pang and are willing to pay these exorbitant amounts to be able to show off their prestige cars.

Rail Network Development

The first railway lines were built by private companies in the second half of the 19th century, with most companies building their own terminus stations. Throughout the 20th century, many stations in the tight urban core were closed and replaced by newer, larger termini further out. This also allowed for the consolidation of railway lines into fewer terminus stations. Limbē-Dyanchezi was opened in 1909 to take over most services to Ozuman Chezi in Daiamondoshi-Pang, Kibō-Dyanchezi in 1929 to replace Humenyamin Chezi, also in Daiamondoshi, and Aku-Dyanchezi in several phases in the 1970s as a replacement for the overburdened old Akuchezi in Doíku-Pang. Starting in the 1960s, suburban commuter trains were connected through the city center via repurposed or newly constructed underground rail corridors.

Public Transit

There is a wide range of public transportation systems enabling inhabitants and visitors of the city to move around without the need for a car. While being operated by several different companies (even excluding niche services such as shuttle busses or sightseeing tours) they can be used using an integrated fare and ticketing system that encompasses all of Pyingshum-iki. This system, as well as passenger information and coordination between the different agencies, is provided by the regional administration of Pyingshum-iki. For public transportation systems aimed at long distances, please refer to Long-distance Rail or Airfare.

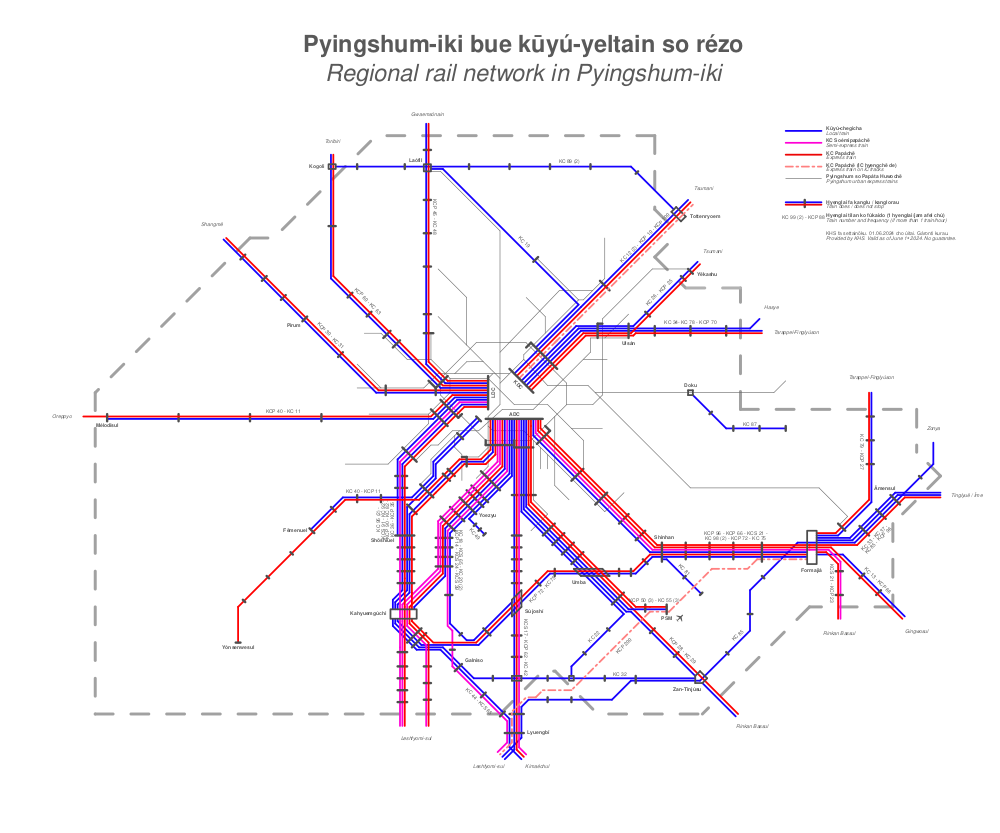

Regional Rail

Regional trains run on regular 1,435 mm gauge railway tracks, often shared with freight or other passenger trains. They are mostly used to travel between different cities and towns. On some relations inside the city, they can be useful as an express alternative to the Papáchē, however all services terminate at one of four terminus stations. On travel-heavy weekends, additional trains are run on KCP 45 and KC 48 which terminate at Paetishózyokael instead of Limbē-Dyanchezi. Regional trains are operated by Kojo Hyengshō Sanan (Kojo Railway Company), which is owned by the national government. Most lines run hourly and follow clock-face scheduling.

Around 1.2 million trips are made on regional trains in Pyingshum-iki per day. Counting passengers transfering between regional train lines only once, 1.1 million unique trips remain.

Papáta Huwochē (Express Trains)

| A | A1: 4 t/h | 20 t/h | A2: 3 t/h | 1.0 mio p/d |

| A3: 4 t/h | A12: 3 t/h | |||

| A5: 4 t/h | A4: 4 t/h | |||

| A9: 4 t/h | A6: 4 t/h | |||

| A11: 4 t/h | A8: 3 t/h | |||

| A10: 3 t/h | ||||

| B | B1: 2 t/h | 20 t/h | B2: 7 t/h | 0.9 mio p/d |

| BX1: 2 t/h | B4: 6 t/h | |||

| B11: 6

t/h |

B6: 7 t/h | |||

| B3: 2 t/h | ||||

| BX3: 2 t/h | ||||

| B13: 6

t/h |

||||

| C | 15 t/h | 0.9 mio p/d | ||

| D | D1: 6 t/h | 20 t/h | D2: 6 t/h | 0.7 mio p/d |

| D3: 8 t/h | D4: 6 t/h | |||

| D5: 6 t/h | D6: 8 t/h | |||

| E | E13: 6 t/h | 18 t/h | E2: 6 t/h | 0.7 mio p/d |

| E15: 6 t/h | E4: 6 t/h | |||

| E17: 6 t/h | E6: 6 t/h | |||

| F | F1: 8 t/h | 8 t/h |

F3: 4 t/h

F5: 4 t/h |

0.2 mio p/d |

| G | G1: 10 t/h | 18 t/h | G2: 10 t/h | 0.6 mio p/d |

| G3: 8 t/h | G4: 8 t/h |

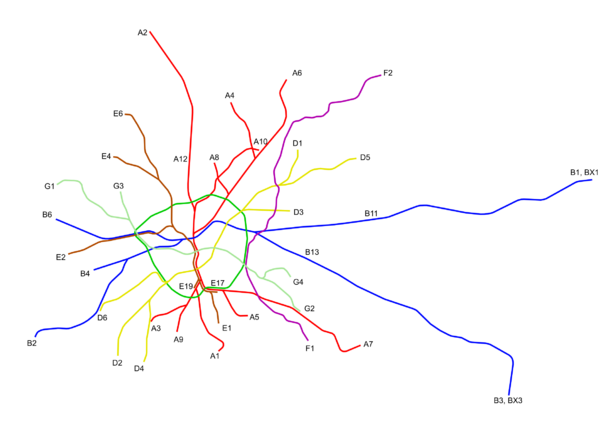

Originating from suburban main line services terminating at the city's terminus stations, the opening of tunnel sections underneath the inner city in the 1960s marked the entrance of the new Express Trains (lit. "Express Liners", Papáta Huwochē or short Papáchē, named in reference to the more local Metro services). As a result, they run on the same type of tracks and electrification as standard main line trains, however the tunnel crossections are incompatible and the two networks are independent in everyday operation. They mostly serve passengers from the suburbs or immediate neighbouring towns who want to travel to or through the city center. While lines A, B, D and E were built and are owned and operated by the Kassulgōsaei Papáta Huwochē Sanan (KPHS, Capital Region Express Train Company), whose shares are owned by the city of Pyingshum as well as other municipalities in Pyingshum-iki served by the network, lines C and F are owned and operated by KHS. This is because the infrastructure of the ring line C and the tangentional line F was developed by KHS out of the circumventional main line ring and a freight bypass in the 1980s and 2000s. Especially the infrastructure of line F is still used by some freight trains today.

Around 5.0 million trips are made on Papáchē trains daily. Counting transfering passengers only once, 3.4 million unique trips remain.

Chitakyoe Huwochē (Metro)

The Pyingshum Metro (Chitakyoe Huwochē, lit. "underground liners", short Chitachē) is one of the oldest underground railways in the world. The network is used to get around the inner city and covers an area approximately equal to the railway ring line. With some older lines operating on narrow gauges akin to tram lines, later lines were built at standard gauge. Tunnel crossections however are much narrower than main line standards, and electrification takes place via a third rail on most lines. The Metro is operated by Pyingshum Kōkyō Susyong Unzuó (PKSU, Pyingshum Public Transport Authority), which is solely owned by the city of Pyingshum.

| Nr | Colour | Length | Stations | Platform | Interval | Ridership | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | 80 m | |||||

| 2 | Orange | 80 m | |||||

| 3 | Yellow | 80 m | |||||

| 4 | Spring Bud | 80 m | |||||

| 5a,5b | Green | 120 m | Self-intersecting circle line, name change at Milaen'yum. | ||||

| 6 | Electric Green | 100 m | |||||

| 7 | Malachite | 100 m | |||||

| 8 | Medium Spring Green | 120 m | |||||

| 9 | Aqua | 120 m | |||||

| 10 | Blue Bolt | 100 m | |||||

| 12 | Blue | 120 m | |||||

| 13 | Electric Ultramarine | 120 m | |||||

| 14 | Violet | 100 m | autonomous | ||||

| 15 | Magenta | 120 m | autonomous | ||||

| 20 | Grey | 100 m | Shuttle service on former A branch. Technical standards of a Papáchē line. |

The first section of line 1 opens in 1898 and connects the planned city expansion from the middle of the 19th century, Daiamondoshi-Pang, to the old town. Until 1905, parts of line 2 and 3 are constructed and line 1 prolonged to the old Akuchezi. In the following decades, the network is expanded at rapid speed.

(Further text TBD)

Shigájanchoel (Light Rail)

Until the 1950s, Pyingshum had a dense tram network serving the inner city as well as some suburbs. With the further expansion of the Metro and the rise of private motorisation and omnibusses, the tram network got cut back over the decades until in the 1980s only three lines remained (modern 17 and 22/24). After cautious reactivation in the 1990s (sections of 25), new lines were constructed starting in the 2000s, mainly to improve access in suburbs where metros are not feasible and alleviate some congested tangential bus routes. The modern network consists of nine lines in five separate networks. While the legacy lines run on a narrow gauge of 1,060 mm, the new lines runs on standard gauge. Like the Metro, all tram lines are operated by PKSU.

Bus Network

Busses are an indispensible part of the public transportation network. Especially in the suburbs they feed passengers to Metro and Papáchē stations. In more central areas, where competition by rail-bound transit is high, there is a wide variety of services to further improve local accessibility or offer transfer-free rides between areas not directly connected by alternative modes of transit. Busses are either operated by PKSU or, especially for services crossing the city boundary, the respective service providers of neighbouring municipalities.

There are sevencategories of bus services with different stopping patterns and service characteristics, each recogniseable from the line code.

| Type | Line code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Bus | 200-599 | Run on intervalls of 10 to 30 minutes, up to 60 minutes in the periphery during fringe hours. |

| Neighbourhood Bus | 1-9 for Dengshō + five letters | Smaller vehicles covering otherwise not well accessible areas with meandering routes and connecting them to a near by transit hub. Frequencies of 15 to 60 minutes. |

| Metro Bus | M + 01-99 + small letter to distinguish leg | Like standard bus, but on a core section very high frequencies (one bus every 1 to 3 minutes) are achieved, usually by overlapping several legs of services, and slightly wider stop spacing. |

| Shuttle Bus | P + 01-99 | Connects areas (usually suburban neighbourhoods without rail connection) and/or high-demand punctual destinations (usually transit hubs) with only few stops inbetween. They often run on motorways for significant portions of the route, where they also have a couple of stops. Usually low frequency of one bus every 30 minutes with several routes overlapping on motorway sections. |

| Event Bus | E + 01-99 | Like Shuttle Bus, but only for the duration of a specific events with high attendence and with higher frequency. |

| Replacement Bus | T + number or letter of replaced line + small letter to distinguish different services | Replaces a rail-bound transit line, usually during maintanance. |

| Night bus | G + number of replaced line or 200-670 | See Night Service. |

Public transport night service

No regional trains run between 1 and 5 am. Notable exceptions are a number of KC services from Pyingshum to large neighbouring cities, which ensures about one to two trains an hour on the important radial main lines.

Papáchē and Chitachē lines run all night on Friday and Saturday, as well as before holidays, albeit on reduced frequency of one to two trains per hour per Papáchē branch and about three to four trains per hour on Metro lines. There is no night service during Sunday night, when all lines are replaced by night busses. During the week, every Papáchē and Chitachē line shuts down for two consecutive days from about 11 pm to 5 am, with the days varying by line, to allow for inspections and smaller repair works. During this time, night busses replace the closed lines with higher frequencies than on Sunday nights.

Most bus lines as well as the Shigájanchoel cease operation at night. To ensure a basic coverage, a less tightly knit network of night busses with different route alignments replaces them. Standard or Metro Busses that do not cease operation at night.

Fares and Ticketing

There is an integrated fare system for all means of public transport within Pyingshum-iki, with the exception of long-distance trains and a surcharge on the KCP 50 to the airport (which employees are excempt of). It is zone-based, with every stop being assinged one or, in some edge cases, two zones. In Pyingshum, zones are numbered from 1 to X, where 2, 3 and 4 form rings around the city center and 5, 6, and 7 are used for more distant suburbs. The rest of Pyingshum-iki is tiled using zones numbered with two-digit numbers. The ticket price depends on how many zones one traverses for a given trip. Exceptions to this rule apply to zones 1 to 4, namely the one-zone-ticket for zone 1 is a little more expensive than the normal one-zone ticket, and for travel between zones 2, 3 and 4, a discount of one zone is given. E.g., travelling from 4 through 3 to 2 only needs a two-zone-ticket, and even travelling from 4 through 3, 2, 1, 2, and 3 back to 4 only needs a three-zone ticket. Any trip that involves only six stops on a bus, three on the metro or shuttle bus, or one on the Papáchē, without changes, can be undertaken using a short-ticket, no matter the zone. Seniors and minors are granted a discount of 50%. For every ticket type there also exists a 24h-pass, a 7-day-pass, and a monthly pass which allows a specific person to travel a specified number of zones from a chosen home zone. They cost 2.5, 9.5, and 29.5 times the amount of a single ticket. Minor and senior discounts apply.

| Zone(s) | Short | Only zone 1 | Only one zone

(not zone 1) |

2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price | 35 | 90 | 75 | 135 | 195 | 250 | 300 | 350 | 400 | 450 | 510 |

Interactive Map (Shigájanchoel, Chitachē, and Papáchē)

Loading map...

Long-distance Rail

As the nation's largest city and main railway hub, most IC and CC lines terminate in Pyingshum. All long-distance trains that serve Pyingshum stop at one of city's three main railway stations (Dyanchezi), CC 370 and CC 780 trains calling only at Zuede-Fuwō Chezi being the only exception.

Airfare

| Terminal and sector | Gates (bridge) |

Gates (bus) |

|---|---|---|

| T1-A | 8 | 10 |

| T1-B | 13 | 8 |

| T1-C (under renovation) |

13 | 8 |

| T1-D | 13 | 8 |

| T1-E | 13 | 8 |

| T1-F | 8 | 10 |

| T1-K (under construction) |

(24) | (2) |

| T1-L (projected) |

(24) | (2) |

| T2-G | 17 | 3 |

| T3-H | 9 | 4 |

| T5-J | 0 | 12 |

| Sum | 94 | 71 |

Pyingshum International Airport, around 50 km to the south of the city center, is the region's principal airport and also functions as a hub and intercontinental gateway for all of Kojo. It served 67.3 million passengers in 2022, making it the busiest airport in Kojo by far both in terms of passenger and freight volume. It is a relatively new airport with its main terminal in the shape of a six-armed starfish. In its center, it features a large tropical garden open to all levels with a cylindrical waterfall entering through an orifice in the roof construction.

The first airport in the city was the Kū A'éropō, opened in the north-east of the city center with a circular airfield in 1916. Its later runway had a usable length of around 1.5 km. In 1939, a second airport was constructed to the south-east of the inner city, named Longte Puechaésa A'éropō. This larger airfield allowed for two parallel runways with a usable length of up to 3.2 km. This became important in the 1960s and onward, when the jet age radically transformed civil aviation and enabled more and more people to fly. The hexagon-shaped main terminal, opened in 1964, is emblematic for that time period and preserved as a historic building to this day. Over the years, as air traffic continued to grow and Kū A'éropō became unfit for most air traffic due to its short runway and noise pollution, more and more side terminals were added at Longte Puechaésa.

It became apparent in the 1980s that further expansions at Longte Puechaésa were unfeasible due to lack of space. Similar to Kū A'éropō, the adverse impacts of noise pollution also became a heated subject of discussion. This also impeded the nation's ability to establish an internationally competitive hub airport. As a result it was decided to construct a large new airport far outside the city boundaries. Quick access to the city and the rest of the country was ensured by planning a dedicated branch line to offer direkt regional train services to the city center and with a high-speed circumvential line, allowing trains from all over the country to bypass Pyingshum with a stop at the airport, already in mind. The first two runways and the first terminal building T5, which nowadays is used by low-cost carriers, opened in 1998. At that point, the airport was only yet accessible by road and bus, as the rail lines were still to be constructed. Still, this added capacity enabled the full closure of Kū A'éropō and the conversion of its airfield into green space and into part of the railway corridor connecting the east of the nation more directly to Kibō-Dyanchezi.

The main terminal building T1 as well as the regional rail connection to the airport opened in phases between 2003 and 2005. This newly added capacity allowed Longte Puechaésa to close for scheduled air traffic in 2004. Consequently, Longte Puechaésa's southern runway was converted into a park area and all side terminals and parking areas were turned into new neighbourhoods and commercial areas. Longte Puechaésa's last runway remains in use for special freight deliveries, government and private flights to this day. The tangential high-speed rail line to the new hub airport opened in 2006 and 2008 to the west and east, respectively. In 2012, Terminal buildings T2 and T3 opened to be primarily used for domestic and short-haul flights. Especially since the 2010s, other international airports in Kojo, most notably Kippa and Yoyomi, experienced a steady decline in passenger numbers due to the large offer of direct flights from the new capital airport and its proximity and high accessibility.

Since 2020, a new midfield addition to terminal 1 is under construction with an expected opening date of 2028. There is also room for an additional second midfield expansion, with demand forecasts indicating demand for such an expansion by the late 2030s. Even more longerm, there are expansion options for T2 towards T1, for a new terminal between T1 and T5 as well as a redevelopment of T5 itself. In 2023, the C arm of T1 is the first arm to be temporarily shut down for a thorough renovation, with the other arms following consecutively.

Shipping

The river Kime is an important route for freight shipping. Passenger ferries play only a very minor role due to the high number of bridges, however there is a large number of sightseeing tours, especially along the scenic river banks in the inner city and the Sunmyuel Tyanhā, as well as a small number of river cruises.

Pyingshum's ports, from north to south, are:

- Moebi Nafahang (1 basin, with rail)

- Kókōburyu Nafahang (4 basins, with rail)

- Chin Tákoechiwe (1 basin, no rail)

- KART Nafahang (1 basin, no rail)

- Sunmyuel Tyanhā, Mómauel-Pang (sightseeing and river cruises only)

- Kansokkuwīdoling Nafahang, Róng'yeda-Pang (2 basins, private yachts only)

- Porāgu-Parishíla Nafahang (11 basins, with rail, Geolymp)

- Éngkai Kū Nafahang (1 basin, recreational use only)

Economy

While Pyingshum accounts for only about a fifth of Kojo's population, its share of the national GDP is almost one third.

Primary Sector

Agriculture, fishing or mining play only a very minor role in Pyingshum's urban economy.

Secondary Sector

While the manufacturing industry accounts for a smaller share in Pyingshum's economic output than other cities in Kojo, it remains a consequential sector overall. Including construction, it accounts for 13 % of the city's GDP and employs a similar share of the workforce. Construction, food and material processing and machinery production as well as niche products contribute over-proportionally to the secondary sector compared to the Kojolese average.

Tertiary Sector

The dominance of the tertiary sector in Pyingshum is even more pronounced than in the rest of the county and other developed nations. It makes up 86 % of the city's economy and employment, with a higher spread of income among workers in this field compared to the primary and secondary sectors.

As a global city, the finance and consulting industry has a strong foothold in Pyingshum. Most larger Kojolese companies have their headquarter in Pyingshum, and the city is the prime location for Kojolese branch offices of international companies. Much of the associated office space is located in the high-rise district Chinkágaldosim-Pang. The Pyingshum Stock Exchange is also situated there. Due to its primacy, Pyingshum is also the nation's largest host of conferences, fairs and leisure events. This is exemplified by various large-scale venues.

Being the most visited city in Kojo, tourism is not only relevant for its directly associated industries such as hospitality, but also for the city's well developed retail, gastronomy, culture and personal service industries. The most pricey retail areas are situated in Daiamondoshi-Pang, where not only the wealthy residents of the neighbourhood themselves but also affluent visitors from all over the world frequent the many exclusive boutiques, delis and jewellers. It is estimated that about 10 million international visitors come to the city every year (spending an average 3.8 nights and 2990 Zubi (130 USD) per night), with an additional 6 million overnight guests from inside Kojo (average: 2.0 nights). The number of domestic day visitors (excluding regular commuters) is thought to be around 40 million, however these numbers are difficult to estimate.

Education and research is also a major economic factor for the city. University students from all over the country and abroad come to study at one the city's many institutions of higher education, both because of their quality of teaching and the high quality of life in the city itself. Consequently, Pyingshum is a highly attractive location for all kinds of research institutions.

Being the nation's capital, the public sector is often assumed to make up a big share of the city's economy. While the national government and parliament contribute heavily to Pyingshum's relevance in Kojo and abroad, for example by attracting a large number of international governmental and non-governmental organisations, public service employment is actually not much higher than in most other cities in the country. This is because for the most part the lower agencies of the national administration, which make up the vast majority of actual employment, are spread throughout the country. The city once calculated that the lower number of children in Pyingshum compared to the national average and the consequentially lower number of school teachers being employed in Pyingshum by the national government in itself alone offsets all employees working in the Chancellery, ministries and parliament. In absolute terms however, the municipal government alone is by far the largest employer within the city, like in most places in Kojo.

The transportation industry also plays a larger than average role in the city's economy. This is mostly due to the high number of logistic businesses as well as the high share of public transportation. As a result, the Pyingshum Kōkyō Susyong Unzuó (Pyingshum Public Transport Authority) is the second largest employer in the city.

Important Institutions

- National and International governmental institutions

- National and International NGOs

- Pyingshum-iki institutions

- Pyingshum-sur institutions

- Iki-embassies

- Embassies: see Kojo#Foreign diplomatic missions in Kojo

Education and Research

Schooling

Higher Education

The city's largest university is Ginjin Ōnagara. 256,900 students are enrolled here. The institution was founded in 1677, at the suggestion of King Surb Rēkku, to strengthen Pyingshum's position in the yet to be unified region of today's Kojo, and was hence named "Rēkku-tami to ishimwaru Ōnagara" (lit. "The University that is owed to King Rēkku"). The old main building is still preserved at Mēonra Nobun'ga Kamul Gúwan in Kūtokkyaen-Pang. After the revolution in 1828, the university was renamed several times until, in 1837, given its current name "Ginjin Ōnagara" ("Free People University"). A new campus was built outside of the city north of Daiamondoshi-Pang, and since 1894 the previous main building is occupied by the Kojolese People's Scientific Society. As the university grew, several new campi around the city were founded. They are not completely congruent with the faculties, but usually most rooms for one faculty are found on one campus, with every campus being able to serve the students' basic needs. The campi are named from I to IIX.

|

|

For an overview over all Universities in Pyingshum and Kojo, please refer to the main article.

Culture and Leisure

Street Culture

Public Events

Green Spaces

Major parks and cemeteries, beaches, environs

- Bikkimolno-Dyangfuē (short "Bikkifuē", Zoo), 1900, Bikkifuē-Pang.

- Guóhuwei-kenzai (Botanical Garden), 1846, Lí-Pan.

Sport and Event Venues

- Pyingshum Exhibition Centre, over 1 million m², 1956.

- Pyingshum Conference Center, 1986, Chinkágaldosim-Pang next to Aku-Dyanchezi

- Bonzai Hall, 1920, Kissha-Pang. Multi-purpose indoor arena, seating around 17,000 people depending on use. Former trade fair hall made of brick.

- Kū Aenkaiwe (Pyingshum Old Stadium), 1958, Wakawushi-Pang. Covers 36,000 m² and seats around 50,000 people. Does not conform with modern standards and expectations for a large international stadium. Mostly used for 2nd league sport matches or as an fallback option.

- STAR Kaijōmengwe (STAR Event Hall), 1989, Kyáoling-Pang. Mass events like concerts, indoor-sport etc. Up 70,000 visitors depending on layout.

- Geolymp. For the 1984 Geolympic Games an industrial harbour area was redeveloped:

- Pyingshum Ashkal Aenkaiwe (Pyingshum World Stadium). Building footprint of 70,700 m², can seat up to 85,000 spectators.

- ASA Hall. 11,000 seats, used for indoor ball sport like Badminton and Basketball.

- Baein-Kamkā Ring, 9,000 spectators. Used for the martial arts competitions during the Geolympic games, now Ice Skating.

- Other facilities (re-)built for the 1984 Geolympic Games include

- Aquatics center, Tai Aku-Hyengkōsa Chezi. 17,000 spectators.

- Dōka Dowe

- Izaland Airlines Hall

- Doldae Onagara

- Humenyamin Arihangwe (Amber Archery Hall)

- Magittā Fuézyadoenwe (Nacre Shooting Hall)

- Éshkim Taitaiwe (Great Fencing Hall)

- Al-Abadi Yaélaimankaikal (Al-Abadi Cycling Race Track)

Museums

- Jōbun Chigai-Showugan (People's Art Museum), 1847, Ōnagara-Pang. One of five national museums, mostly Kojolese and some foreign artists of all periods

- Modan Chigai-Showugan (Museum of modern Art), 2002, Gankakuchō-Pang. Contemporary art.

- Jōbun Lishi-Showugan (People's History Museum), 1888, Goengyuē-Pang. One of five national museums, dedicated to the national history

- Pyingshum Lishi Showugan (Pyingshum History Museum), 1964, Kūtokkyaen-Pang. Museum dedicated to the history and development of the city, inside old town hall building.

- Chénbyue Showugan (Château Museum), 1944, Kūtokkyaen-Pang. Former palace of the Pyilser-krun'a dynasty that was left in ruins since the revolution. Open-air museum about the obsolete Kojolese monarchy, ticket building inside the former royal household agency.

- Kojo-UL30c Hakubutsukan (Kojo-UL30c Museum), 1980, Kūtokkyaen-Pang. Explorering the relation between Kojolese and UL30c's history and culture in the past and present.

- Ashkal so Lánche Whowugan (Museum of the World of Insects), 1913, Lí-Pang. Adjacent to the Botanical Garden.

- Demomínzu so Showugan (Democracy Museum), 1976, Goengyuē-Pang. Located at the People's Square next to Parliament.

- 1984 so Ōkurā nijúinde Showugan (Museum dedicated to the Great Fire of 1984), 1991, Gankakuchō-Pang. Museum accompanying the memorial site.

- Shínchopō so Showugan (Museum of the Constitution), 1942, Daiamondoshi-Pang. Located on the central circus, exhibitions about the Kojolese and other international constitutions.

- Sukálpuchā nijúinde Showugan (Sculpture Museum), 1996, Ōnagara-Pang. Located in the Fíngmaru Kenzai.

Performing Arts

- Kū Gekkwae (Old Theatre, former Royal Theatre), 1812, Kūtokkyaen-Pang, 480 spectators

- Jōbun-Myeru so Gekkwae (Theatre of the Republic), 1839, Daiamondoshi-Pang, 1130 spectators

- Gēshusamnengwe (Opera House), 1860, Senjahi-Pang, 1950 spectators

- Pétanyaé Gekkwae (Pretanic Theatre), 1897, Hintajuemba-Pang, 650 spectators

- Yínyuē-Taitaiwe (Concert hall), 1901, Goengyuē-Pang, 2850 spectators

- Yamamoto Katarelichigai-Kaiwe (Yamamoto Performing Arts Center), 1978, Mómauel-Pang, 2970, 570 and 260 spectators in three halls

Libraries and Archives

- Zággai Besoegawan (National Libary), 1944, Kami so Kuruchi-Pang. Most comprehensive library in Kojo, hosting one print of almost every Kojolese publication ever made since its opening as well as a large international collection.

- Ashkal so Besoegawan (World's Library), under construction, Kami so Kuruchi-Pang. Project by the World-Archive Organisation, aiming to collect and safely store compressed hardware-backups (such as in the form of quartz-chrystals) of the world's great scientific and poetic literature, news and artworks.

- Zággai Altífō (National Archive), 2003, PH-Pang. Dedicated to storing and preserving all unique objects of value to Kojolese cultural or historical identity that are not on exhibit in art museums or similar. Ranging from war machinery to mummies and earth probes.

- Sulchaedaeki Altífō (City Archive), unknown, Kūtokkyaen-Pang