Mauretia

|

Royal Dominion Mauretia Melkanas Mauretia (Maurit) Capital: Iola (de facto)

Population: 13,947,823 (2021) Motto: « Qi bardrea Eloe sum Mauroim » Anthem: « Imnos al-Eloe » |

Loading map... |

Mauretia, officially the Royal Dominion of Mauretia (Maurit: Melkanas Mauretia), is a country located in southwestern Uletha along the Sea of Uthyra. It borders Sathria to the north and UL205b to the east. The largest city is Iola, which also serves as one of the nation's most prominent port cities. Its largest port is in the second largest city, Tangia. Mauretia's government is a constitutional parliamentary monarchy with powers split between the head of state and the parliament. The seat of the legislative branch and most government facilities are concentrated in Iola; but the monarch resides at the Regia Daneloza∈⊾ in nearby Qolna Mauretana. Mauretia is also a very religious country, and its state religion is an indigenous branch of the Christic movement. Freedom to worship and proselytize other faiths is guaranteed by the constitution, and there remains a small pagan minority that has seen a revival of practices since the 1700s.

Mauretia was first settled by Ponqtai, Fonti, and Azigri peoples in antiquity. They established trading colonies around the region. Its strategic minerals and fertile coastal lands made it an ideal place for Hellanisian and later Romantish expansion. Mauretia was on the far fringes of the Romatish empire, when it was conquered in the second century BC during a brief war. The native Azigri and Fonti populations became heavily Romantisized by the time their trading network collapsed in the late 5th century. The sub-Romantish kingdoms in Mauretia survived the turbulent next two centuries until unification took place in the 7th century by King Akasil and his daughter, Queen Daya. Daya's work expanded and promoted the fledgling trade links, and Mauretia quickly emerged as a major regional sea-faring power. Despite some civil strife in the 12th–15th centuries, Mauretia has remained a monarchy and remained oriented to trade. Over the last two centuries, the nation has fostered a highly developed banking system along with a blooming fishing industry, stable mining industry, and growing production in chemical and pharmaceutical sectors.

Etymology

The name Mauretia is derived from the Romantish word "Mauretiana" that itself was likely a corruption of Marro and Maszaéa, two of the most prominent Azigri tribes of antiquity. The name Mauretia became synonymous with the entire coastal region and eventually was ascribed to the different sub-Romanti kingdoms. As a result, it became the name of the unified kingdoms in the seventh century. The term Mauroi evolved similarly from the name of the Marro tribe and eventually became a demonym of the entire population. Even though the words are often viewed as interchangeable abroad, the government officially uses the term "Maureti" to refer to the nation and its institutions and "Mauroi" to refer to the nation's citizens. The word Maszaéa evolved into the toponym of the province Massaeya.

History

| History of Mauretia | |

|---|---|

| Pre-unification | (before 667) |

| • Romantish puppet dynasty of Mauretiana | c. 150 BCE |

| • Romantish Mauretiana | 40–459 |

| • Unification Wars | 615–667 |

| Unified kingdom | 667–1533 |

| • Daya crowned "Queen of the Mauretianas" | 667 |

| • Treaty of Sala | 721 |

| • Succession War | 1241–1245 |

| Modern kingdom | 1533 |

| • Reign of Avigela IV | 1505–1551 |

| • Current constitution | 1533 |

| • Treaty of Iqosa | 1831 |

The area of Mauretia was first settled sometime before the tenth century BC by tribes of Azigri origins. Most of their settlements were along the coasts and in strategic valleys. In the fifth century BC, a coalition of Ponqtai and Fonti trading tribes settled the coastal areas. They constructed trading colonies at modern Tangia, Luxedira, Iola, Iqosa, and Iomna. From here, their trade spread across the western part of the continent and northern Tarephia, even as far south as modern Brasonia and brief contact as far east as Kojo. A few Hellanisian outposts were attempted during this time, as well. Tasaqora, Qiza, Lissa, and Pomalia were all established during a second period of Ponqtai and Fonti expansion, from the late fifth century BC to the second century BC. Mauretia's natural resources, wealthy cities, and location along the Sea of Uthyra made it a target of Romantish merchant expansion. By the 2nd century BC, Romantish raiders and merchants had seized control of most trading locations along the coast but failed to establish many new cities. Instead, they unified the area as "Mauretiana" under a puppet dynasty. Even so, the rugged terrain and stretch military resources prevented the Romantish leagues from directly controlling much of the country's interior. A coalition of native peoples in the mountains and highland plains acted outside of the "Mauretianan" realms. Ethnic tensions boiled over after the first 50 years of quasi-Romantish coastal control. A brief but devastating war subdued the military resistance of the different native peoples along the coast, but it also weakened the ability of the puppet government to dominate trade routes into the interior. The Romantish fully invaded in 40 AD, deposing the weak "Mauretianan" dynasty. To hold control, they divided the region into the provinces of "Mauretiana Tangirensis" (south) and "Mauretiana Azigriensis" (north) roughly along a line from Assigium (As-Siga) to Suroris Magna (Num-er-Surora). Capitals were established at Tangia and Iola.

Under Romantish rule, only a limited number of peoples from further afield in the empire relocated to the Mauretian provinces. A few legions were permanently stationed at outposts such as Qasratinta or Num-er-Surora, and land grants were occasionally gifted to warriors and merchants as payments. Some cities, like Salda and Bolubra, were designated for settlement by Romantish veterans and their families, thereby changing the makeup of the city. These were exceptions, however, and not the norm. On the whole, it is estimated that only 1⁄12 of the current population's genome is of Romantish ethnic origins. Despite the lack of immigration, the Romantish exercised outsized control over the area's culture. Large swaths of native Azigri and Fonti populations became heavily Romantisized during this time. The exchange of goods and knowledge between the groups had assured this intermixing. The local dialects of Azigri went extinct in the coastal regions, and the Fonti languages fell out of use as well. Both form a recognizable substrate in the present Maurit language. The Romanto-Azigri peoples eventually became the dominant local players in the culture, government, and economy of the provinces. Their dominance was especially seen in religious circles, where the local pantheon never yielded to Romantish deities. The Ponqtai, however, resisted the Romantisization; they remained isolated in a few coastal cities through the fifth century AD. Eventually their language and cultural traditions were absorbed into the larger proto-Maureti environment. Some desert-based Azigri tribes also remained largely un-Romantisized, preserving their languages and some traditions in the arid regions of the Maureti interior for a few additional centuries.

The Christic movement arrived in the last couple years of the first century AD. According to legend, two ancient apostles were responsible for bringing the faith to Mauretia. They were met with initial success in Tangia, which has remained the seat of the Patriarchate of Tangia ever since. Subsequent missions to the coastal cities found very limited success. The less urban-dominated Azigri interior, however, took hold of Christicism quickly. By about 150, it was said that only the more Romantish coastal cities in Mauretia were not fully evangelized. This quickly changed in the first half of the third century, as Azigri culture continued to infiltrate and influence the cities. From the Romanto-Azigri tribes came some great pillars of the early Christic faith, like Saint Abastinus. A conflict within the southwestern Ulethan churches, however, came to the fore in the early fifth century. The Patriarch of Tangia was nearly anathematized and the Mauroi Church reciprocated by rejecting some of the other Hellanisian and Romantish leaders. After many years of tension, two reformist saints bridged the gap between the two patriarchies to allow for a peaceful separation. The Mauroi Church has remained "separate but cooperative" with the Ekelan Churches since. It retains very close ties with this sister church through the patriarchate in Sirsi, Egani with similar liturgies and practices. Culturally, Egani and Mauretia retain many close ties to the present. Discourse with Ortholic churches in the Mediterranean basin resumed in the 1750s, and a mutually-beneficial heterodoxic acceptance has taken hold.

The last half of the fifth century AD brought the a widespread economic collapse to Mauretia. Long-range trade links beyond northern Tarephia and the Liberan Peninsula failed. Romantish imperial domains collapsed, leaving the remaining wealthy aristocracy to their own devices. The large Romantish-Azigri and Romantisized Fonti populations revived suppressed tribal divisions, and the church, still reeling from its recent crisis, was powerless to step in. The 480s were a time of fierce civil war as various tribes attempted to assert control in the new power vacuum. Fighting broke out within a few ethnically mixed city-states as well, furthering the economic collapse. A wave of migrating barbarian incursions also destabilized the region. A turbulent decade unfolded as various groups worked against each other to secure dominance and ward off primarily north-Ulethan and proto-Mazanic barbarian and pirate activity. By 500, over a dozen successor states had arisen. The next century saw the region rebound economically and culturally; many of the various states banded together with intricate alliances with varying levels of suzerainty. About 630, King Akasil of Pomalia began the process of peacefully unifying a few surrounding lesser principalities and duchies that had been subservient to the Pomali crown. His realm included almost all of central Mauretia from Bolubra north to Tinyarita. Akasil waged war against Lissa, Iola, and Iqosa during his reign. All three were under Eganian-sponsored gubernatorial control. He conquered Iqosa but perished in the battle against Iola. His daughter, Queen Daya, acceded to the throne in 667 and immediately made peace with Iola for two years. She also strengthened her ties with the Kabyei kingdoms of Iomna and Salda. She called her kingdom "Mauretia" as part of her attempt to unify the remnants of the two former Romantish provinces. Daya invested great effort and money into expanding and promoting the fledgling trade links with central Uletha and southeastern Tarephia. Many of the Romantish-period roadways, which were still in service, were restored and straightened where necessary; she commissioned a new port in Iqosa and facilitated treaties with Salda to reopen trade links. Her navy quickly emerged as a major sea-faring power in the region. It maintained commercial and cultural contact during this period with other thalassocracies as far away as Kojo. Her dominion abounding in wealth and power, Daya petitioned lesser kingdoms to be annexed and create a regional power. Some kingdoms, like Lissa and Luxedira agreed. Others, such as Iola and Xovane did not. She went to war with those that did not join her dominion and quickly subdued them. Instead of wiping out the cities, as her father pledged, she only eliminated the aristocracy of the conquered cities; she rebuilt the urban centers to her liking and strengthened their hold. The independent city of Tangia, which was ruled by the Patriarch of Tangia, agreed to annexation after the fall of Iola on the condition that the church retain a say in the government. The final piece was the independent kingdom in Salda, which controlled the northern coastline. After a series of peaceful diplomatic exchanges and a royal marriage, Daya was able to annex the kingdom piece by piece. In the end, she had unified all the Mauroi kingdoms into one regional power. Although deposed aristocracies occasionally rebelled, the new Kingdom of Mauretia remained a stable presence.

Mazanic incursions in the seventh century were a constant threat to the Maureti kingdom. This forced the construction of new defensive lines in the desert and a stronger navy. Mazanic armies did briefly capture a few cities in the southwestern part of the country, such as Anba and Amitye; these were only held for a few short years, however. Consistent raids and naval slave impressment brought Mauretia to war with Mazan multiple times through the eleventh century. In 1070, Iola was attacked by a huge naval presence. A portion of the old city was set ablaze, but heavy monsoonal rains suddenly arose and helped to suppress the fire. A series of horsemen raced to Tenya and Tifassa to rally what portion of the navy could be mustered. The small, outnumbered naval Maureti naval force ambushed the Mazanic raiders from behind and trapped them in the Port of Iola during the continuing deluge. The ensuing battle was a complete rout, and Mazanic seafarers avoided attacking Mauretia for another 200 years.

The monarchy did have some turbulent periods on the domestic front in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries, however. Various pretenders, monarch deaths under suspicious circumstances, rulers of questionable legitimacy, and open rebellion in the Lawa Valley threatened to destroy the kingdom. King Gergio III initially arose at age 15 as a weak king in 1241 during an uprising in Lissa and surrounding cities. Historians note that his claim to the throne was murky at best—one of his two older cousins likely should have been crowned—and had been orchestrated by coup-minded advisors. Gergio was initially an unwilling participant in the schemes of his advisors, whom he had inherited from his uncle. As the conflict with his cousins and southern rebels went into a third year, he grew tired of the manipulating and scheming. He quickly moved to secure his throne militarily and economically: he sacked all of his predecessor's advisors, executing seven of them for high treason; crushed the rebellion; defeated one pretender; and personally met with another, his cousin Habrino, to make peace. The king and his cousin agreed to peace as part of a series of reforms that reorganized provincial domains, granted some private land rights, created plebeian mayoral positions in cívitam, and reworked the judiciary to be more just. The agreement also decreed the unusual requirement that Habrino's infant son would be heir to the crown unless the unmarried Gergio had two daughters, in which case the second daughter was designated heir. To perpetuate the peace 23 years later, Gergio's second daughter, Lucia, ascended to the throne and appointed Habrino's son, a skilled warrior named Yosef, as her top general.

Another round of insurrection arose among the populace in the early sixteenth century. After a minor civil war, Queen Avigela IV was crowned as part of the peace treaty. Deeply religious and reform-minded, she swept out many in the aristocracy, sacked much of the now-corrupt judiciary, relocated the palace to just outside Sansu Andaros su Apostili, and orchestrated the drafting of the constitution-like document the Logenatiu in 1533. Initial signatories were the queen herself, the Patriarch of Tangia and three of his metropolitans, all the provincial governors, all five of the remaining aristocratic families, and the plebeian mayors of nineteen major cities. The document not only secured the monarchy, it gave a voice to the populace as a check against the government. Historians note that the move to create a full parliament with checks on monarchial power was very forward-thinking, even though only a simple legislative body was formed. The primitive checks-and-balances system allowed Mauretia to withstand many waves of revolution that swept across other parts of Uletha, as the monarchy was largely viewed as at least in part subservient to the broader will of the people. Although some changes have been made over the years, the core structure and fundamental delineation of power remains to the present.

Trade with northwestern and central Uletha waned substantially again in the 13th centuries, but Mauretia's strategic location on the Sea of Uthyra allowed it rebound soon thereafter. Mauro merchant tribes looked afield to see potential colonization sites in the 15th century, but it was not until the later half of the century that they were able to establish trading colonies in quarters of preexisting cities. Mauretia was periodically thrusted to the forefront of various conflicts against colonial powers, such as the Plevians, Valonians, Ingerish and Castellanese. Castellán attempted an invasion of Mauretia in the 1450s but was only able to take a few coastal cities, all of which were returned via conflict over the following decade. Mauretia struck a peace treaty with the Castellanese to prevent further conflict with the fall of ally Pohenicia. The Patriarch of Tangia, who personally controlled the monastic Gorgaya Islands, asked Mauretia to take possession of the islands in the 1600s after Plevian merchants had attempted to set up a merchant colony. In the 1700s, Castellán revised its peace treaty with Mauretia, causing the latter to not intervene in the invasion of Dematisna; Mauroi Christics in Seniqe were guaranteed recognition and security, Castellán was also granted some trade rights in Tangia, and Mauretia was gifted half of Saint Josefa island and trading rights in the Lycene area. Trade and the economic power of Mauretia diminished again in the late 19th century as decolonization occurred. Economic ties with numerous countries, however, remained strong and were a springboard to expanded diplomatic relations throughout Tarephia and Archanata.

Mauretia's economy collapsed in 1873 with an unusually lethal influenza outbreak. Called the "Great Death" (Su Mawaṭo Arrabo), the strain of influenza afflicted as much as 70% of the Mauroi people and killed more than 25% of the country's population. The origins of the outbreak are unknown, but it is believed to have originated elsewhere in Uletha or northern Tarephia as other countries experienced its effects first. Regardless, Mauretia was particularly hard hit. The population under the age of 30 suffered dramatic reduction second only to those over 60. The death of so many young Mauroi hampered population growth for generations. The military was decimated; nearly 60% of those in active duty were killed or suffered long-term effects that forced retirement. As a result, the nation adopted a view of neutrality to the potential conflicts unfolding around it. Its geographic position away from most of the fighting helped the declared neutrality be respected. Out of the epidemic, however, came an incredible number of medical advances. The government heavily invested in the scientific study of the disease. Germ studies launched in Mauretia, and the country helped pioneer the idea of disease spread by bacteria or viruses. It also became a leader in experimental studies for pharmaceuticals. The "Great Death" ultimately ushered in a new economy less reliant on international trade and more open to scientific study and advancement. Official government policy was created to encourage larger families and growing the population. It created revolutionary policies such as paid maternity leave and expanded education. After three decades of political and cultural challenges caused by the societal shift, the birth rate recovered. The changes revolutionized Mauretia. The nation developed a high birth rate among industrialized countries and has been slowly increasing. Today, Mauretia still boasts a highly developed banking system along with a blooming fishing industry, stable mining industry, and growing production in chemical and pharmaceutical sectors. Its medical scientists are among the most sought after in the world.

Government and politics

| Government of Mauretia | |

|---|---|

| Constitutional parliamentary monarchy | |

| Capital | Iola (de facto) |

| Head of state | |

| • Melka (Queen) | Gabriela III |

| • Duttore al-Qoncilo | Benyamin Danosioi |

| Legislature | Parliamentad Mauretia |

| • Upper house | Qoncilo ad-Publea |

| • Lower house | Qollegia am-Adunem |

| Judiciary | Yudicio Superioru |

| Patriarch of Mauretia | Baba Bittorio I |

Major political parties | |

PDK PQ ALL PMM AT Bm PF | |

| AN, ASUN (partner state), IWO, PAR, SJC, UU (observer state) | |

See also: Government of Mauretia

See also: Government of Mauretia

Mauretia is one of the oldest continuous monarchies in the world, having been established in the seventh century. From its early years, an advisory council has existed in conjunction with the monarch to guide the ruler in decision making and to reflect the will of the people. By the eleventh century, this body had grown to be corrupt. A series of revolts nearly toppled the monarchy in 1241, whereupon King Gergio III instituted reforms that sacked the advisory council and instituted the first representative body, made up of popularly elected delegates from every diocese. Although this body wielded no specific powers, Gergio III effectively created the predecessor to the country's modern parliament. Fifty years later, King Gergio IV saw that only aristocratically connected people were winning elections and split the council into two separate houses: a lower house, where the people were directly represented by commoners, and an upper house, wherein the military, church, and aristocracy chose the leadership. In the fifteenth century, King Okem V unilaterally instituted reforms that allowed for the upper house to contain a representative from each province's directly-elected parliament as a further means of checking aristocratic power.

The modern Maureti state evolved in the sixteenth century, when Queen Avigela IV instituted sweeping reforms that flipped the roles of the two legislative houses and codified the relationship of the crown and the parliament in the Logenatiu of 1533. Those directly elected were given substantial legislative power as the new upper house of parliament; a degree of checking power was placed with the aristocratic, now lower, house of parliament. The upper house also gained the right to overrule the monarch and to force abdication in extreme circumstances. Additional constitutional changes are extremely difficult and can only be done as an act of unity between the monarchy, parliament, provincial governments, and popular referendum. The monarch and the parliament are effectively prohibited to propose structural changes, and either the provinces or the populace must agree to debate a change in order for it to reach the national level.

Government structure

Mauretia is a constitutional parliamentary monarchy with executive and legislative powers shared by both a strong monarch and a bicameral parliament. The monarch serves as Head of State, Commander-in-Chief of the military, and has the responsibility to appoint the prime minister and justices. This position is currently held by Melka Gabriela III, who is a descendant of the House of Sansu-Andaros and ascended to the throne in 2003. Also vested in the crown are the abilities to craft law, with subsequent parliamentary approval, and dissolve parliament. The monarch must have an heir to the throne at all times. In the event the heir is not 17 years old, a regency from the lower house of parliament intervenes in a limited capacity. Notably, gender has never been a determining factor for succession since inception of the monarchy. The current heir is Nura, daughter of Melka Gabriela III.

The prime minister is head of parliament and is leader of the Qoncilio ad-Publea (Public's Council). The holder of this position is selected by the monarch from a parliament-approved list of no less than ten sitting members. The prime minister's cabinet is selected without interference from the monarch, and the position has the right to request the dissolution of parliament or force a potential national vote of abdication. This position commands the legislative process and works directly with the monarch. Powers include dictating the agenda of parliament's upper house and selecting a cabinet. The cabinet members convene with the prime minister to discuss policy, craft agenda, and set a course for the government. They also head the different parliamentary committees and have a tie-breaking vote in each. The current prime minister is Beniyamin bon Dangisos, who represents the diocese of Emka Asmina.

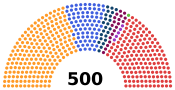

The Qoncilio ad-Publea is comprised of 500 members, who are voted directly from the populace and represent a riding. They are limited to serving three total terms in office and must retain full residency in their home riding. In all, the Qoncilio can legislate by passing a bill with a simple majority. Within one week, the monarch decides to grant consent (enacting the bill into law) or deny. Should the monarch deny the bill, her veto can be overridden by a two-thirds supermajority in the Qoncilio. The lower house of parliament, the Qollegia am-Adonem, is comprised of around fifty members, with some variability to monarch appointments. They represent the aristocracy, the provincial parliaments, the Mauroi Church, and the monarch. The power of the lower house is largely ceremonial but may be constitutionally instructed to intervene in the absence of a monarch with severe limits on their powers.

The judiciary remains independent and functions separately from the executive and legislative processes other than appointment to the judicial seats by with Qoncilio approval. Justices serve for a maximum of twenty years in their position. After the twenty year period, the monarch elects to reappoint the justice or offer a new appointment to the Qoncilio. Historically, justices under the age of 70 have been reappointed without difficulty.

Capital

Mauretia has no single city defined as the capital according to the Logenatiu. Officially, the capital is vested in the monarch, which most legal scholars define as wherever the ruling monarch is at any given moment. From an administrative perspective, however, Iola∈⊾ serves as the de facto capital in many ways. It hosts the entire legislative branch and most executive offices. Iola also houses the majority of embassies and Maureti offices of international organizations. As the largest city, it is also a financial and educational hub of the country. The monarch primarily resides in an independent administrative district called Qolna Mauretana∈⊾, about 34 kilometers east of Iola. The main royal palace has been located here since 1684. The judicial capital of Mauretia is in Pomalia, and Tangia is defined as the ecclesiastical capital.

International relations

Mauretia is a middle power that has taken a moderately active role on an international level. The country is neutral but rejects pacifism. It has diplomatic missions in over two dozen countries, and it sponsors the International Center for Mauroi Culture as a secondary diplomatic enterprise. Mauretia is a member of the Assembly of Nations and participates in many AN–sponsored and affiliated organizations. Mauretia hosts the Ulethan office of Red Shield and a branch office of the International Women's Organization. With its national focus on culture and cultural development, Mauretia was a founding member of the Ulethan Alliance for Culture in 1980. Mauretia has also been a partner state of the Association of South Ulethan Nations since 2001. Public policy has resisted full membership in the organization, fearing forced changes to the country's long-held neutrality, encroaching secularization, the opening of borders without adequate checks, or any international agreement that would supersede popular sovereignty. The country's politics lean "Ulethoskeptic," and there have been notable calls for the country to leave ASUN altogether.

Administrative divisions

| |

|---|---|

| Administrative divisions of Mauretia | |

| First-level | 6 probinciam 1 royal district 1 external territory |

| Second-level | qolnam and diosim |

| Third-level | cíbitam, urbim |

See also: Administrative divisions of Mauretia

See also: Administrative divisions of Mauretia

Mauretia is divided into six provinces and one special administrative district. The provinces are Kabyea in the north, Massaeya in the near north, Rifaleya in the west-central, Aziga in the eastern part of the country, Tangereya along the southernwestern coast, and Dara Aqarel in the southeast. Each province is divided into diosim (dioceses) and qolnam (independent cities). Each diocese is in turn made up of cities, towns, and villages. The independent district of Qolna Mauretana is a separate administrative division solely inhabited by the royal family. It houses the royal palace, a cathedral, and a few important government buildings.

Officially, Mauretia consists of two external territories (Mauretia Externaya):

- The Gorga Islands (Ilm Gorgaya) sits in the Sea of Uthyra, about 300km south of UL02d. Only two of the three small islands are populated, and the majority of the population is monastic or otherwise tied to the monasterial lands. Each monastery on the island is directly overseen by the Patriarch of Tangia; other citizens on the island do elect a single Member of Parliament for representation.

- Saint Yosefa island (Sansa Yosefa) has been split since the late 1700s, after the northern part was granted to Mauretia as part of a peace treaty. Mauretia attempted to release the island or allow it to be unified with San Marcos on three separate occasions, but all referenda were resoundingly for continuation under the Maureti crown. About 95% of the Holmic population on that part of the island is Mauro Christic, and religious concerns are the primary motivation to remain unified with Mauretia. Given the notable population but also the tremendous distance between Sansa Yosefa and the Maureti mainland, this territory has its own parliament and judicial system that is overseen and governed by the Monarch directly. Maurit and a local Holmic dialect are both spoken on the island. A non-binding referendum in 2005 voted by a small majority to change the status of the island from an external territory to a true province, even though it would subject the island to the national parliament and judicial system. The monarch has yet to give ascent to the referendum results.

Geography

| |

|---|---|

| Geography of Mauretia | |

| Continent | Uletha (Western) |

| Region | Ghetoria |

| Population | 13,915,327 (2021) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 201938.50 km2 77968.89 sq mi |

| • Water (%) | 2% |

| Population density | 68.91 km2 178.47 sq mi |

| Major rivers | Asmina, Lawa, Malba |

| Time zone | WUT+2:30 (MST) |

Location

Mauretia is a country in along the Sea of Uthyra in southwestern Uletha, bordered by Sathria to the north and UL205b to the east. Because Mauretia is bisected longways by the 45th east parallel, it uses the offset time World Time +2:30. From a geological perspective, Mauretia sits on three continents: the mainland is in western Uletha, the external Ilm Gorgaya are part of a Tarephian tectonic plate, and external territory of Sansa Yosefa is part of the Antarephian continent.

Topography

Occupying one side of a peninsula, Mauretia is dominated by its coastline and prominent mountain ranges. These mountains are generally rocky and covered in scrub or thin evergreen woodlands. In between many of the ridges are wide valleys with fertile ground. These areas tend to be ideal for vineyards, meadows, groves, and orchards. The higher hills are used for shepherding and poultry farms. Mauretia's western coast is often rocky with numerous inlets and few natural beaches. Large boulders and extreme rock outcroppings litter the densely wooded landscape. The southern shore is defined by its fertile coastal plain. Notably, the rivers of Mauretia are not navigable far inland. Mauroi sailors have long mastered the difficult shores and water outflows, which has been vital to the country's trade and maritime industries.

Climate

| Iola | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mauretia has a wide range of climate patterns from coastal Mediterranean areas to arid deserts east of the High Adlar mountains. Generally, the transitional seasons are wet, warm, and short. The coastal areas and the low-profile plains of Tangereya and Rifaleya fall into the hot-summer Csa category with savannah-like wet–dry pairings (Aw) in the far south. Some interior ranges near the coast are cooler (Csb). Much of northeastern and east-central Mauretia is semi-arid (BSh/BSk) with cooler temperatures (Dsb) along the highest peaks of the High Adlarm. Along the eastern border is open desert-lands. Rainfall and snowfall is plentiful enough in the wet seasons for a productive agricultural returns, with the climate most conducive to growing fruits, vegetables, and beans. Vineyards and orchards are common throughout the countryside. Sitting south of 30°N, Mauretia frequently experiences southwesterly-flowing tradewinds from the deserts in the east toward the coastal areas. When the subtropical ridges of the horse latitudes increase over eastern Sathria, this helps spur the yearly monsoonal rainfalls in most of western and southern Mauretia. The Harm Adlarm cause uplift of wind blowing off the Sea of Uthyra and creates frequent precipitation. Grains, including millet, oats, wheat, and amaranth grow well with widespread rainfall through the winter months and a minor monsoonal season in the late summer.

With its position on the globe, Mauretia can be susceptible to extreme weather conditions. Some locations in the mountainous areas of the country can receive over two meters of snow in a given winter. Sudden blizzard-like squalls have been known to produce a half meter in one day. Cloud cover is also common in the late summer as monsoons begin, and some Maureti cities are known as among the cloudiest in region during these months with sunshine during less than 50% of daylight hours. Heat waves in the peak summer can be as high as 45° have been recorded in July and cold spells with temperatures as low as −11° have been recorded in February. With the tradewinds from the dry northeast, temperatures can plummet in the winter and the air may be as dry as 15% humidity. The dryness may cause negative health effects to vulnerable populations. Outbreaks of severe weather, such as tornadoes are known to happen and can be strong, although they are far more common in the southern portion of the country than in the north. Heavy rainfall can also occur in the wet seasons, causing flooding along the mountain valleys. Even interior cities, like Pomalia, experienced severe flooding in 1953 that displaced nearly half of its then-177,000 people. In the highlands, the first frost occurs around early October; final frost is often in late April to around the first of May.

Demographics

| Demographics of Mauretia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demonym | Maureti | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Maurit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognized minority languages | Azigit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ethnicities | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Religion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literacy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Life expectancy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The official population of Mauretia, according to a government census in 2013, was 13,773,698. There are an additional 103,000 people in Mauretia on economic or academic visas that are not counted in the census. The nation features a relatively high birth rate for an industrialized nation at 19.7 per 1,000 inhabitants and has been increasing in recent years. The nation has not been below replacement-level fertility in over a century. Life expectancy is about 79 years. These factors have contributed to a growing population, which is projected to exceed 17 million by no later than 2030.

Mauretia differs from many other nations with regards to the roles of women in society. While religious, military, and merchant sectors have most frequently been dominated by men, women have long had an important role in the culture, political system, and economy. Many of Mauretia's rulers were women. Female literacy has historically been higher than male literacy; literacy was not considered extremely important to military or agrarian sectors. Yet, education of women was considered paramount as a means of continuing the culture, values, and knowledge to younger generations as they were being raised. Throughout the middle ages, Mauroi women equally contributed to scientific advancements and cultural output. Only in the seventeenth century did the education of men for all walks of life become important. This distinct view came to the fore again in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Due to international conflict and need for productivity after sweeping diseases, Mauroi women began to take on increasing roles in the workforce and economic diversification began. By the 1920s, policies were put in place to try and balance family life and increased economic output. After a couple turbulent decades of stagnant population growth, the culture adapted and evolved. The marriage and birth rates recovered and the societal change has promulgated through to the present. As a result, there remains no stigma against women in nearly any sector of culture or economy. Some of Mauretia's most prominent intellectuals and artists of the last 500 years have been women, and in recent years women have been among the wealthiest business owners in the nation. Men only tend to dominate careers as farmers, shepherds, or miners. At the same time, women athletes are among the best in the world and their sports generate as much revenue as many male sports. Two of the most popular professional sports leagues in the country are women's leagues.

Ethnicity

According to the census, 97.1% of the nation's population self-reported as ethnically Mauro. (The Holmic population of Sansa Yosefa is counted separately.) Of this percentage, about 2.5% was foreign born. The largest other ethnic groups included Eganians (1.1%), Pohenicians (0.7%), Kazaris (0.5%), and Serionics (0.4%). Notable populations of Antharians and Mazanics are also present in larger coastal cities. Immigration to Mauretia is not particularly high, but no government policy actively discourages it. The country's net-migration only turned positive in the last forty years, and there remains a substantial Mauro diaspora overseas. Many immigrants to the country have come from neighboring states for religious or economic reasons. Iola, for example, has nearly 35,000 Kazari Christics that are descendants of Christic refugees from the 1910s. There has also been a broader trend in recent years among Mauro young adults repatriating from overseas.

Studies of the ethnic Mauroi population show common traits with a window of genetic variability among the people group. A recent physical-traits study in 2015 of nearly 730,000 Mauroi people estimated that 78% of the Mauroi population had brown or dark brown hair, with medium/dark blond and auburn as common variants—each at about 5.5% of the population. Among that same group sampled, 83% had brown eyes, with 10% registering blue or grey and 7% green or other heterochromia. Height among Mauroi people can vary, and extremes are found. Even so, the average height of men and women are very close in proximity. Men average 175.0cm in height, while women average 167.9cm in height.

Religion

Mauretia is officially a Christic nation, and the Logenatiu defines the indigenous Christic branch as the official religion of the nation. This understandably affects numerous aspects of Mauroi culture and society. Freedom to practice any faith publicly or to proselytize is assured through the constitution, but proselytization is socially difficult. Other Christic denominations and religions have arrived in Mauretia over the years but remain a small minority in the country, generally confined to larger cities. Officially, the Mauro branch of the faith is "separate but cooperative" with its sister churches. It retains very close ties to the Ekelan Church in spite of a schism in the fifth century. The Mauroi that remained in communion with the Ekelan churches in Egani and other nearby lands reformed their congregation into the small "Nodasic" Church. The term "Nodasic" comes from the old Maureti word meaning "tied together."

The largest non-Christic religion is neo-Paganism based on modern forms of Mauro polytheism. This particular belief system has become quite popular among otherwise secularized repatriates, comprising up to 25% of that demographic. Mauro polytheistic practices from antiquity are among the best documented in the world. The religious practices of ancient pagans were all but wiped out in the seventh century, but the combination of academic scholarship and historical site preservation has allowed it to remain. Because some sites, such as the temple and cave complexes to the god Asese are on preserved lands, neo-Pagans have accused the Christic government with discrimination and religious suppression. The only Pagan practice that is explicitly outlawed is the ancient practice of child sacrifice. Generally, access is granted to Pagan groups without restriction provided that these groups do not damage the historic site. Most important locations, such as the Temple of Time, have been divested from the public land holdings and are simply registered sites that must be preserved by the ownership groups, similar to historic Christic basilicas or monasteries.

Language

The official language of Mauretia is Maurit. The language is a member of the southern branch of the Romantish Uletarephian language group. Although Romantish supplanted the local languages in the second and third centuries, the local vulgar dialect retained an immense influence from Hellanisian and Semetic languages. Combined with Serionic contact, Maurit evolved to contain a large Serionic, Hellanisian, and Semetic substrata. Even a few grammatical features of the language, such as the standard verb–subject–object (VSO) word order are due to the large influence from the ancient languages of Ghetoria. The language has a standard form regulated by Sa Qollegia ad-Maurit. Standard Maurit is the official form used in government, media, and education. The Qollegia also recognizes three principal dialects (northern, southern, and eastern) and provides a standardized form for them, recognizing differences in word choice and spelling as viable alternatives to the standard form. There are few differences between northern, eastern, and southern dialects of the language. The eastern dialects tend to be the most distinct on account of the geographic isolation in the Ghetorian desert.

The last census recorded that 98.7% of Mauretia's mainland citizens speak Maurit as their first language. A small community of Azigri speakers still remain in the interior desert communities. Their language is officially protected in status with mechanisms in place to provide facilities in government, education, and religion in the Azigri language. It is spoken by only a few hundred people as a first language in the last census. The government officially promotes bilingualism among the two Azigri tribes in the region, but the use of the language has continued to wane. In the external territory of Sansa Yosefa, a Maurit-influenced dialect of Holmic is spoken by 79% of the citizens as a first language, while 17% speak Maurit as a first language. Over 95% of citizens on the Maureti part of the island are bilingual in Holmic and Maurit, and bilingualism is officially taught in schools. Other languages known to be spoken in Mauretia include Eganian, Sathrian, and Antharian.

Territory-specific topics

| |||

Regional topics

| |||

Global topics

| |||