Government of Mauretia

| Government of Mauretia | |

|---|---|

| Constitutional parliamentary monarchy | |

| Capital | Iola (de facto) |

| Head of state | |

| • Melka (Queen) | Gabriela III |

| • Duttore al-Qoncilo | Benyamin Danosioi |

| Legislature | Parliamentad Mauretia |

| • Upper house | Qoncilo ad-Publea |

| • Lower house | Qollegia am-Adunem |

| Judiciary | Yudicio Superioru |

| Patriarch of Mauretia | Baba Bittorio I |

Major political parties | |

PDK PQ ALL PMM AT Bm PF | |

| AN, IWO, PAR, SJC, SUCC (observer), UU (observer) | |

The government of the Royal Dominion of Mauretia is a unitary state with one of the oldest continuous monarchies in the world. The country is a constitutional parliamentary monarchy with some devolved powers to provincial and local governments. The monarchy was first established in the seventh century and gradually evolved with reforms in the eleventh, thirteenth, and sixteenth centuries to form its present constitutional system. The current constitution, the Logenatiu of 1533 remains in force with a few amendments that have been added over the last five hundred years. Under this constitution, Mauretia operates with a strong monarch as chief executive, with shared legislative powers, and an independent judiciary.

History of governance

Mauretia was established in the seventh century under Queen Daya, who unified a large number of regional city-states and rural tribes into a single domain. Daya divided the land into provinces largely along lines of the pre-unification states but had removed much of the aristocracy. This created an initial vacuum that gave rise to a new era of local leaders and wealthy families. The provinces were subsequently divided into diosim (rural areas with scattered settlements and minor cities) and qolnam (large cities that required more direct administrative intervention). The monarchy changed little in the first four hundred years. An advisory council often existed in conjunction with the monarch to guide the ruler in decision making and to reflect the will of the people. By the eleventh century, this body had grown to be corrupt and was known to act as a shadow government to ensure aristocratic power and wealth. A series of peasant revolts turned into a full-scale civil war that nearly toppled the monarchy in 1241.

King Gergio III began his reign in 1241 amidst the uprising and having been installed by corrupt advisors inherited from his uncle. Over three years of fighting, he realized that the aristocratic council was manipulating the conflict and playing both sides to their advantage. He quickly moved to secure his throne and then preceded to sack the entire council, including executing seven of them for high treason. After quelling the rebellion, he instituted reforms that reorganized provincial domains, granted some private land rights to commoners, created plebeian mayoral positions in cíbitam, reworked the judiciary, and called for a representative of every diocese to be elected by the populace directly to serve on a new council. Although the elected officials wielded no specific powers, Gergio III had effectively created the predecessor to the country's modern parliament. The council was extremely disfunctional at first, as competing interests from across a large territory sought to have the ear of the crown. Amidst the chaos, local aristocrats would bribe leaders to control the strings of the council. This was often done openly. The council lasted only fifty years before King Gergio IV faced a similar series of insurrections against the aristocracy. To quell the masses, the elder statesman split the council into two separate houses: a lower house, where the people were directly represented by land-owning commoners and tribal clan leaders with term limits and strict prohibitions against bribes, payoffs, and grants; and an upper house, wherein the military, church, and aristocracy chose the leadership. The upper house was established as such, because its recommendations and declarations were considered to have primacy; it could reverse the lower house declaration by a two-thirds supermajority. In 1403, King Okem V unilaterally instituted reforms that created provincial parliaments to advise governors and required that each of these bodies send an elected representative to the upper house. This was a further attempt to check aristocratic power. It was now too difficult for most regional aristocrats to payoff both members of a national body and numerous local bodies.

The modern Maureti state evolved in the sixteenth century. Queen Avigela IV became the mother of the modern Maureti state with sweeping national reforms. Avigela IV was a traditionalist who romanticized the eras of the distant past. She saw the waves of anti-monarchy sentiment brewing around various parts of Uletha and believed in pushing toward a more historic model of government that reflected on a combination of city-state democracy and the strong Mauro tribal-familial structure. At the same time, she equally distrusted the aristocracy and believed that it was her greatest internal enemy. In 1531, she swept through massive changes to the government structure. Avigela IV's first reform was to alter the country's administration. She made all devolved powers to provinces and municipalities uniform instead of the hodgepodge that had been carved out by influential regions or aristocratic families. The provincial governments were charged with working with the church to register births, marriages, deaths, and family tribal affiliations. This allowed the queen to have a census of all family heads—patriarchs and matriarchs alike. Her second reform was to grant suffrage in local, provincial, and national elections to all family heads regardless of land-owning status or clan hierarchy. With a robust electorate, she took inspiration from antiquarian city-state democracies and instituted direct municipal and provincial elections. Devolved powers away from the central government were very limited and were, in fact, more restrictive in some ways. The devolution was made uniform across the entire country to ensure the strength of the crown as the ultimate authority and no region or aristocratic family with clout had extra power. The directly elected upper house of parliament was chosen by vote of family-head commoners. Now a year into the reforms, Avigela IV heard numerous rumors that the aristocracy were seeking to depose her. She escalated her reforms, centralizing the military under the crown and stripping most aristocratic privileges. Next, she flipped the roles of the two legislative houses, so that the substantial legislative power was vested with the commoner-elected upper house of parliament; only a small amount of checking power was placed with the aristocratic, lower, house of parliament. Taking a cue from Mauro tribal-council traditions, she continued her reforms by devolving some balancing power away from the monarch. The upper house was granted the right to overrule the monarch with a large supermajority vote and to force abdication in extreme circumstances. A series of other reforms ensured an independent judiciary, limits on aristocratic power, the strength of the monarch as both executive and in the legislative process, and the ability to limit further reforms unless initiated by the population at large. All of Avigela IV's changes to the government structure were codified in the Logenatiu of 1533. With new limits in place, it fixed the core of the governance system almost entirely into its current form. A score of amendments have passed over the years to adapt to changing times. The most robust change to have occurred since Avigela IV's reign was the widening of suffrage to all family heads beyond those tribal-defined in the 1680s and full universal suffrage for all citizens 19 and older in 1818. Among other changes: term limits for parliament were added in the 1860s to prevent a political aristocratic class from forming, and the administrative state was affirmed as an extension of the monarch's power but now requires a degree of legislative oversight.

Government structure

- In accordance with Mauroi etiquette and tradition, the monarch in this section will use feminine pronouns on account of the current ruler being female. Likewise, pronouns for the Prime Minister in this section will be masculine.

Mauretia is a constitutional parliamentary monarchy with executive and legislative powers shared by both the monarch and a bicameral parliament. The government operates under the rules established by the Logenatiu of 1533. The monarch serves as Head of State and Commander-in-Chief of the military. She has the responsibility to appoint the prime minister and justices. Also vested in her are the abilities to craft law and dissolve parliament. The prime minister, however, is the official leader of parliament and must be selected from among the sitting members. He chooses his own cabinet without interference from the monarch, and he has the right to request the dissolution of parliament or force a vote of abdication. The judiciary remains independent and functions separately from the executive and legislative processes other than appointment to the judicial seats.

Role of the monarch: executive and legislative

The monarch is the Maureti Head of State. This position is currently held by Melka Gabriela III (since 2003), who is a descendant of the House of Sansu-Andaros. She is the face of the nation abroad and is considered the primary representative of the Mauroi people. She is also sole commander of the Maureti military and her representatives alone are able to negotiate peace in times of war. Additionally, the monarch wields considerable powers over the legislative process. One power is the ability to select the prime minister. Restrictions are in place, however, as the prime minister must be a seated parliamentarian chosen from the ruling coalition government. The coalition provides the monarch with a list of no less than ten preferred representatives from which she chooses the head of parliament. There is no secondary approval of the prime minister, and he can be removed without notice at the discretion of the monarch. Likewise, she has the ability to dissolve parliament and force elections. This can take place for any reason but cannot be done more than twice in a 16-month period without a formal request from parliament itself. The monarch must have an heir to the throne at all times during her reign. The heir is historically a child or family member of the monarch but can be an alternatively designated individual. In the event the heir is not 16 years old, a regency from the lower house of parliament intervenes in a limited capacity. To avoid this, monarchs have historically designated condition-restricted individuals to serve until the heir is of age. Gender has never been a determining factor for succession since inception of the monarchy. The current heir is Nura, daughter of Melka Gabriela III.

Legislatively, the monarch has two avenues of power. One power is the ability to enact a royal edict. In order for an edict to become law, it must first be approved by a majority of votes in the upper house of parliament, the Qoncilio ad-Publea. The prime minister has a deadline of either three weeks from the date on the edict or the end of the parliamentary session—whichever is soonest—to bring the edict before parliament for a vote. Should the prime minister fail to bring it before the parliament, it goes immediately to the lower house. A vote is held there immediately. If the edict fails at this point, it is no longer available. If the edict fails to carry in the upper house of parliament, the monarch can request a vote by the lower house. In this body, a two-thirds supermajority is required to cause the edict to become law. If the lower house passes the edict, the Prime Minister has 24 hours to reconvene a vote in the Qoncilio to overturn the lower-house approval. Here, a three-fourths supermajority is required to block the edict from becoming law. The second way the monarch can enact a law is by decree. Decrees are different from edicts in that they need no legislative approval. Their issuance is immediate and permanent but only effects matters considered ceremonial, festive, or monetary donations to causes from the discretionary budget. For example, a decree can be issued to honor a famous artist by placing him in a guild order or to declare a holiday in honor of a famous event. A decree can also be issued to grant money from the monarch's discretionary budget to research at a medical center or to renovate a historical monument.

Role of parliament and the prime minister

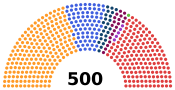

Parliament is made up of two houses. The upper house is the Qoncilio ad-Publea (Public's Council), and the lower house is the Qollegia am-Adonem (College of Lords). Power is very asymmetrically divided, with most reserved for the upper house. The lower house is largely ceremonial in nature but does play a crucial role if invoked by constitutional procedure. Both houses of parliament meet at the Parliamentary Palace (Paladias Parliamenta) in the "new" government district that was constructed in 1901. Parliamentary offices surround the public square. The former meeting place was at the ![]() old parliamentary building complex.

old parliamentary building complex.

The Qoncilio ad-Publea is comprised of 500 members, who are voted directly from the populace and represent a riding. They are limited to serving three total terms in office and must retain full residency in their home riding. The members of parliament generally belong to a political party and caucus with either the ruling coalition or the opposition. The prime minister is head of parliament and is leader of the Qoncilio. He commands the legislative process and works directly with the monarch. His powers include dictating the agenda of parliament's upper house and selecting a cabinet. The cabinet members convene with the prime minister to discuss policy, craft agenda, and set a course for the government. They also head the different parliamentary committees and have a tie-breaking vote in each. Like the prime minister, the leader of the opposition in parliament leads the debate against the ruling coalition. The opposition leader also appoints a shadow cabinet that works parallel to the cabinet but without its special powers. The shadow cabinet members are second in command for each parliamentary committee and represent the opposition therein. In all, the Qoncilio can legislate by passing a bill with a simple majority. Within one week, the monarch decides to grant consent (enacting the bill into law) or deny. Should the monarch deny the bill, her veto can be overridden by a two-thirds supermajority in the Qoncilio.

The lower house of parliament, the Qollegia am-Adonem, is comprised of approximately fifty members. They represent the aristocracy, the provincial parliaments, the Mauroi Church, and the monarch. As mentioned above, this house may be called upon to override a parliamentary veto. They can also vote to approve a bill if the monarch is unavailable before the mandatory time-period to approve or reject a bill completes. Even so, the monarch can immediately suspend their approval upon her return, beginning the monarchical veto process. This body also serves in a direct advising role to the monarch but has been stripped of most other legislative abilities. Notably, the Qollegia may act as a regency council in the event the heir is not of age to take the throne. In this instance, it appoints a triumvirate from its members to fulfill the role of the monarch in limited version. At least one must have been appointed to the house of parliament directly by the monarch. The intention is to ensure the legislative process continues, but it is neither allowed to appoint new Qollegia members nor issue decrees and edicts.

The prime minister has one crucial reserve power in that exists as a check against the monarch. The prime leader can call for a vote of abdication. In this instance, parliament votes whether or not to force the monarch to abdicate the throne. If the vote succeeds, the monarch is afforded one month to appeal the vote to the populace or transfer power to the heir. An appeal prompts a national referendum asking whether the monarch should remain in power or abdicate. If the populace votes for abdication, the monarch has one additional month to transfer power. This power has been invoked four times since 1533 and passed parliament each time. In two instances, the populace voted for abdication on appeal. In the event of abdication, the designated heir takes the throne. The current prime minister is Beniyamin bon Dangisos, who represents the diocese of Emka Asmina.

National judiciary

The judiciary is comprised of justices that are appointed by the monarch and approved by the Qoncilio. Justices serve for a maximum of twenty years in their position. After the twenty year period, the monarch elects to reappoint the justice or offer a new appointment to the Qoncilio. Historically, justices under the age of 70 have been reappointed without difficulty. The Yudicio Superioru is located in Pomalia, unlike most government facilities. This court is the ultimate judicial authority in the country. While the high court can censure a monarch for constitutional crimes, it cannot depose. Below the high court are a collection of courts that administrate within defined land boundaries. Appeals courts are immediately below the high court and exist in the capital of every province with jurisdiction defined by the provincial lines. Regional courts are the next administrative layer, and they cover localized collections of municipalities. There are five regional courts in each province. Below the regional courts are circuit courts, with one for every diosi and qolna. The number of judges that sit on regional and circuit courts is defined by a formula based on population. In the event population shrinks and the court size must change, the judge with the least seniority is removed. Justices do not have to live within their judicial circuit, but they must live within their respective region or province.

Government facilities and capital locations

Mauretia has no single city defined as the capital. According to the Logenatiu, the capital is vested in the monarch herself. Some legal scholars believe this means that the capital is defined as wherever the monarch resides; most believe, however, that the capital is actually defined as wherever the ruling monarch is at any given moment. From an administrative perspective, however, Iola∈⊾ serves as the de facto capital of the country. It hosts the entire legislative branch and most executive offices. Iola also houses the majority of embassies and Maureti offices of international organizations. As the largest city, it is also a financial and educational hub. The monarch continues to reside in an independent administrative district called Qolna Mauretana∈⊾, about 34 kilometers east of Iola. The royal palace has been located here since 1684 and is administratively separate from the province of Massaeya. The judicial capital of Mauretia is in Pomalia. Tangia is officially set apart as the ecclesiastical capital.

Prior to the creation of the Logenatiu in 1533, all governmental operations were located in or around the centrally-located settlement Sansu Andaros su Apostili. With the governmental reforms in the early sixteenth century, most operations moved to Iola except the judiciary, which migrated to Pomalia. The royal palace was moved from Sansu Andaros su Apostili to Sansa Avigela in 1684. As the country grew in the twentieth century, government facilities started to relocate around the country as space was needed. The military, for example, houses most of its naval power in Iqosa.

Royal residencies and other facilities

The primary royal residence is the Regia Daneloza∈⊾ in Qolna Mauretana∈⊾. The monarch typically spends the majority of the year at this location. The monarch has two royal properties in Iola, the Paladia Odeya∈⊾ and the Paladia Ospiri∈⊾. The Paladia Odeya is located somewhat near to the legislative hub but is most commonly used as a museum and tourism location. The Paladia Ospiri is known to be a frequent residence of Princess Nura and is commonly used for royal dinners with diplomats or government officials. The primary urban residence of the crown was at the Paladia Aliria∈⊾ until 1860, when it converted into a legislative building by the crown to be used as a temporary home for parliament. It was converted into a museum in 1902 but remains a crown property for the intermittent use of hosting state guests.

Although not an official residence, the crown maintains a secure facility in Iola at the Qasra Sansu Andaros en-Ispuliana, overlooking the city. The Qasra Sansu Iàqobo∈⊾ is a former secure site that has since been converted into a museum.

Government institutions

Although there is shared legislative power between the monarch and the parliament, the executive function lies primarily with the crown. The various government institutions, therefore, are directly accountable to the crown itself. The Prime Minister's cabinet is made of members that take on a full and detailed oversight role in each ministry, but the appointment to head each rests with the crown itself. As a matter of practice, it is not uncommon for the crown to consult parliament for most ministries or even appoint cabinet members directly. Within each ministry are many agencies, however, and while those are appointed by the crown, their appointment must be approved by the parliament and are term limited.

The various ministries that exist are as follows:

- Foreign Ministry

- Finance Ministry (Alminecares Financa)

- Justice Ministry

- Ministry of Agriculture (Alminecares Agriqulcera)∈⊾

- Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Alminecares Qummerciu u'Industria)∈⊾[1]

- Ministry of Culture (Alminecares Qulcera)

- Ministry of Defense and Home Affairs (Alminecares Protegaido u'Afarim Domèstiqo)∈⊾

- Ministry of Education

- Ministry of Environment

- Ministry of Public Works (Alminecares Publiqandam)∈⊾

- Ministry of Science and Innovation

- Ministry of Tribes and Families

- National Academy of Health and Medicine (Aqademias ak-Saludo u'Medigena Nationala)

- Transportation Ministry (Alminecares Zulpiegi)[2]

International affairs

Mauretia is a middle power that takes on a moderately active international role. It strives to be a visible participant in international affairs but also tries to be a voice of balance. Mauretia is avowedly neutral in international conflicts and has been a common historic meeting place for peace negotiations. During the Great War, Mauretia honored its basic international obligations to allies but refused to be an active participant in the war. At the same time, Mauretia rejects pacifism and maintains a robust military for self-defense and peacekeeping. It has diplomatic missions in over two dozen countries, and it sponsors the International Center for Mauroi Culture as a secondary diplomatic enterprise. Mauretia is a member of the Assembly of Nations and participates in many AN–sponsored and affiliated organizations like ANESCO, Organisation Planétaire de Santé, International Sea Justice Court, Global Meteorological Organisation, and International Seismological and Oceanographic Research Council. Mauretia hosts the Ulethan office of Red Shield and a branch office of the International Women's Organization. Relations are sponsored through the Sibling Cities of the World. With its national focus on culture and cultural development, Mauretia was a founding member of the Ulethan Alliance for Culture in 1980. Mauretia has also been a partner state of the Association of South Ulethan Nations since 2001. Public policy has resisted full membership in the organization, fearing forced changes to the country's long-held neutrality, encroaching secularization, the opening of borders without adequate checks, or any international agreement that would supersede popular sovereignty. The country's politics lean "Ulethoskeptic," and there have been notable calls for the country to leave ASUN altogether.

Bilateral and multilateral relations and embassies

| Country | Maurit name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aden | Adenia |

|

| Ambròisia |

| |

| Anṭaria |

| |

| Ardencia |

| |

| Bayu |

| |

| Brasonia |

| |

| Qasteraya |

| |

| Template:Castilea Archantea | Archanteya Qasterana |

|

| Template:Dematisna | Dematisna |

|

| Soldanaria Demiranai |

| |

| Deùdeqa |

| |

| Drabanca |

| |

| Template:Egani | Egania |

|

| Exaya |

| |

| Istaṭim Federalim |

| |

| Fridemia |

| |

| Gobrasania |

| |

| Gwaya |

| |

| Izakia |

| |

| Kalm |

| |

| Kawu |

| |

| Kofuku |

| |

| Koʒo |

| |

| Template:Lorredion | Lorredona |

|

| Template:Lustria | Lustria |

|

| Malesoraya |

| |

| Malliorska |

| |

| Mozanaya |

| |

| Mesiùna |

| |

| Merga |

| |

| Nabenna |

| |

| Ingeraya Nufa |

| |

| Template:Neo Delta | Nyoṭelda |

|

| Plebia |

| |

| Template:Pohenicia | Pohenicia |

|

| Qennes |

| |

| Suraya |

| |

| Tigeria |

| |

| Union of Anglesbury and Youcesterland and the Most Southerly Lands | Aurangeya |

|

| Vodeo |

| |

| Template:Wyster | Ulsta |

|

| Zalbinska | ||

| Antarephian Coalition | Qoncilio Antarefai |

|

| Egalian Union | Unione Egaliai |

|

| EUOIA | Qongresset Ratue ar-Soberaneyam Trattadiam en-Uleṭa (QRSTU) |

|

| Tarephia Cooperation Council | Qoncilio Tarefai |

|

Intergovernmental organizations

| Organization | Maurit name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Qoncilot ad-Natiom (QN) |

| |

| Associu ad-Natiom en-Austruleṭa |

| |

| Ulethan Alliance for Culture (UAC) | Fotùas Qulcera Uleṭoi (FQU) |

|

International Center for Mauroi Culture

The International Center for Mauroi Culture is a cultural organization and secondary diplomatic institution sponsored and run by the government of Mauretia in cooperation with private enterprise. The primary mission of the facility is to provide a cultural space abroad for the advancement and display of Mauroi culture, while also offering educational, economic, and artistic programs to their respective communities. There are currently locations in the capitals of Aorangëa, Brasonia, Mergania, New Ingrea, and Vodeo. Every facility features locations of the hypermarket Oli! and the diner called Manragama. Each cultural center also houses a theatre sponsored by the youth-arts organization Li Tivqui and a teleMaura news bureau that covers that country and, in the case of the New Ingrea and Vodeo locations, the region. Some locations feature the bakery and confectionery chain YemYem and Frotta Bar café. Notably, the Aorangëa location is a smaller facility; as a service to the expat community in Whangiora, the cultural center sponsors the locations of Frotta Bar, Li Bar Tobin, Oli!, and Viroso in buildings adjacent or across the street from the center proper.

| Location | Map | Cultural Center | Art Museum | Cultural Museum | Cultural School | AZO (Bank) |

Frotta Bar (Café) |

Li Bar Tobin (Bar) |

Li Tivqui (Theatre) |

Manragama (Restaurant) |

mediaMaura Bureau (News Office) |

Oli! (Store) |

Viroso (Bookstore) |

YemYem (Bakery) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bărădin, |

Map | |||||||||||||

| Campo Verde, |

Map | |||||||||||||

| Odrava, |

Map | |||||||||||||

| Freistat, |

Map | |||||||||||||

| Kingsbury, |

Map∈⊾ | |||||||||||||

| Arta, |

Map | |||||||||||||

| Whangiora, Union of Anglesbury and Youcesterland and the Most Southerly Lands | Map | |||||||||||||

| Saviso, |

Map |

Notes and references

Territory-specific topics

| |||

Regional topics

| |||

Global topics

| |||